Can Cash Transfers Increase Women’s Grassroots Political Participation? Survey Evidence From Pakistan

Over the past two decades, Pakistan has experienced a ‘paradigm’ shift in its approach to social protection (Gazdar, 2011). Prior to the creation of the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), the Government of Pakistan had little experience implementing a national social safety net. Since its establishment in 2008, BISP, which is currently under the umbrella of the Ehsaas Programme, has provided direct cash transfer payments to over five million women and their families amongst the poorest and most excluded segments of the population. Despite frequent opposition to the program’s explicitly political name, it has in fact expanded with two changes in incumbency in 2013 and 2018. The success of the program has led all three of Pakistan’s main political parties, the PPP, the PML-N, and the PTI, to claim political credit for its successful implementation.

BISP is the first social welfare program in Pakistan to have developed a formula-based approach to poverty targeting. A poverty census was conducted in 2010, forming the country’s first poverty registry. This data was used to compute a numeric score for each surveyed household to determine program eligibility.

In addition to poverty alleviation, gender empowerment is a core goal of the BISP cash transfer program. In fact, a striking feature of the program, in a country with large gaps in women’s access to public life and services, is its targeting of low-income women. However, rigorous evaluations of the program’s effect on gender empowerment and women’s political engagement are relatively rare (Cheema et al. 2016, Ambler & DeBrauw 2017).

Our research focuses on whether receipt of a regular government cash transfer can lead to other positive spillovers on female program recipient’s political participation. Studies on the political effects of cash transfer programs in Mexico and Brazil, have shown that cash transfers mobilize program recipients to vote, and reward parties who they associate with providing these benefits (De La O 2013, Zucco 2013, Baez 2013, Schober 2019). Cash transfer programs that have created direct linkages between the state and citizens have also played a role in undercutting the role of local political brokers, who play an important role in mediating patronage.

Many programs in Latin America are conditional cash transfers (CCTs) that make payment contingent on program recipients sending children to school or getting their families immunized. The BISP cash transfer, in contrast, is an unconditional transfer (UCT), requiring no such interaction between citizens. There is little evidence that UCTs have similar positive political effects (as CCTs) on strengthening citizen-state linkages in similar settings, particularly for women who face multiple constraints in accessing public spaces and services.

We examine whether the BISP cash transfer program has increased female program recipients' political participation along three dimensions: 1) voting in elections, 2) engaging with elected representatives and 3) accessing the local state. We also investigate if cash transfers could reorient citizens away from traditional political intermediaries such as landlords (zamindars) or informal local governance bodies (panchayats) that continue to play an important role in rural areas.

Our research leverages a natural experiment and a ‘regression discontinuity design’ emerging from BISP’s targeting mechanism. The 2010 poverty census assigned all surveyed households a poverty score based on a weighted average of household assets and demographic characteristics. The Government set a cutoff score of 16.17 (eligible beneficiaries have a score of 16.17 or less) to provide coverage to 20 percent of the poorest households.

We interview 2254 BISP beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries in the provinces of Sindh and Punjab in 2019, within a bandwidth of four points around the eligibility threshold. Beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries within this bandwidth can be considered similar prior to the introduction of the cash transfer program, with almost identical levels of education and household assets. Differences in political participation of beneficiaries after receiving the cash transfer, compared to that of the non-beneficiaries within this narrow bandwidth, can be directly attributed to having received the cash transfer.

We first test if the BISP program led to increased national identity cards (NIC) registration. NICs are a gateway citizenship document, required to access several political and social rights, including voting and obtaining government services and benefits. Pakistan has significant gender gaps in national identity cards (NIC) registration, exacerbating women’s exclusion from political participation and access to public services (Cheema et al 2021).

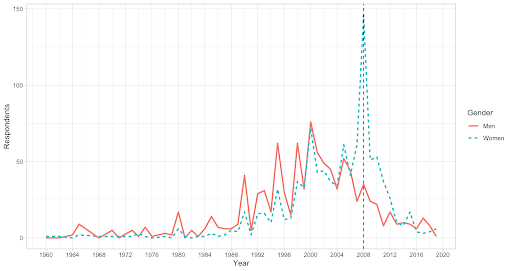

NIC registration is also a requirement to verify identity for the BISP cash transfer. This may have incentivized many women to register for NICs, aided by government efforts to provide women in rural areas with easier access for registration. This is indeed what we see in our data. Figure 1 plots the year in which survey respondents obtained their NICs, and shows, the gap between men and women with CNICs our sample before the BISP was introduced in 2008. In 2008, there is a sharp increase in NIC take up for women, with about 15% of the women in our sample obtaining a NIC that year.

Figure 1: Year of respondent access to Pakistan National Identity Card

Source: Author calculations using sample data from BISP population

Even though the majority of BISP beneficiaries we survey associate the cash transfer with the late prime minister Benazir Bhutto, our results show no significant evidence of increased electoral returns for the original benefit giving party, the PPP, nor for subsequent incumbents: the PML-N in 2013 and the PTI in 2018. The lack of electoral returns suggests the program’s technocratic targeting does not create captive clientele. In fact, we find evidence that the program enables its recipients to freely express their political preference (s) and vote for a variety of parties, particularly in the more politically competitive districts of the Punjab.

In our survey, we find evidence that the BISP cash transfer insulates beneficiaries and their families from traditional patrons who mediate local governance. We ask all respondents if they engage with traditional intermediaries to solve a variety of personal issues, such as access to basic services, credit and employment. We focus on interaction with landlords and village panchayats, two traditional forms of governance that are still prevalent in many parts of rural Pakistan. Our findings illustrate important subnational variation in the type of patronage systems from which BISP beneficiaries are insulated. For instance, in Sindh, beneficiaries report less engagement with landlords who dominate local governance, compared to beneficiaries in Punjab.

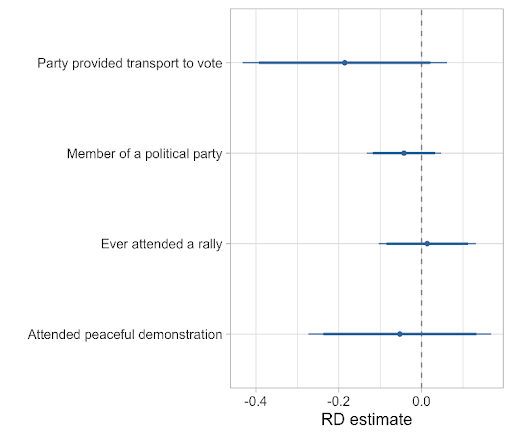

However, financial autonomy from local patrons has not generated increased interaction with local government and political parties. Both beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries report very low levels of direct contact with their elected representatives beyond national voting cycles (Figure 2). A very small section of respondents report attending party events or engaging with party workers apart from on election day. In qualitative interviews many female respondents report finding local government (Union Councils) to be male dominated spaces that are largely inaccessible to them. As a result, though our survey indicates that rural women are increasingly active voters, their lack of direct interaction with political parties reflects an entrenched political strategy whereby parties continue to engage exclusively with men, who continue to act as gatekeepers of women’s political preferences in Pakistan, as in other parts of South Asia (Goyal 2019, Cheema et al 2021, Prillaman, 2021).

Figure 2: Reported interactions between citizens and electoral representatives

Source: Author sample

Our findings have important implications for policymaking. First, we find that technocratically designed cash transfers, such as BISP, do not create clientelist voting even in settings where voters have low levels of political knowledge. In fact, results suggest that the cash transfer provides recipients some degree of financial autonomy from local patrons, possibly due to the reduced need for immediate credit that creates economic relationships of dependency.

Second, BISP’s centralized design and implementation has created few grassroots forums for female program recipients to engage directly with the state. Research in other contexts, where women’s mobility is constrained to the household and bound by patriarchal norms, shows such forums can be crucial for women’s political network formation and collective action (Sanyal 2009, Prillaman 2021).

Third, our research suggests there is a tradeoff between technocratic welfare program designs to avoid concerns about local patronage, and the need for the state to decentralize power to become more accessible and accountable to its’ citizens. In India and Brazil, social policy expansion has coincided with the democratization of local government. In India, for instance, local government reform mandated specific quotas to increase women’s representation and participation (Ban and Rao 2008, Beaman et al 2010). On the other hand, in Pakistan, local government remains a weak and male-dominated space, inaccessible to a large segment of female citizens.

Cash transfer programs such as BISP may have been vital financial lifelines for female beneficiaries and their households, but our findings suggest that they cannot mitigate some of the structural constraints women face in becoming more active rights-bearing citizens.

Rehan R Jamil, PhD candidate, Brown University

Matteo Iudice, PhD candidate, Brown University

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.