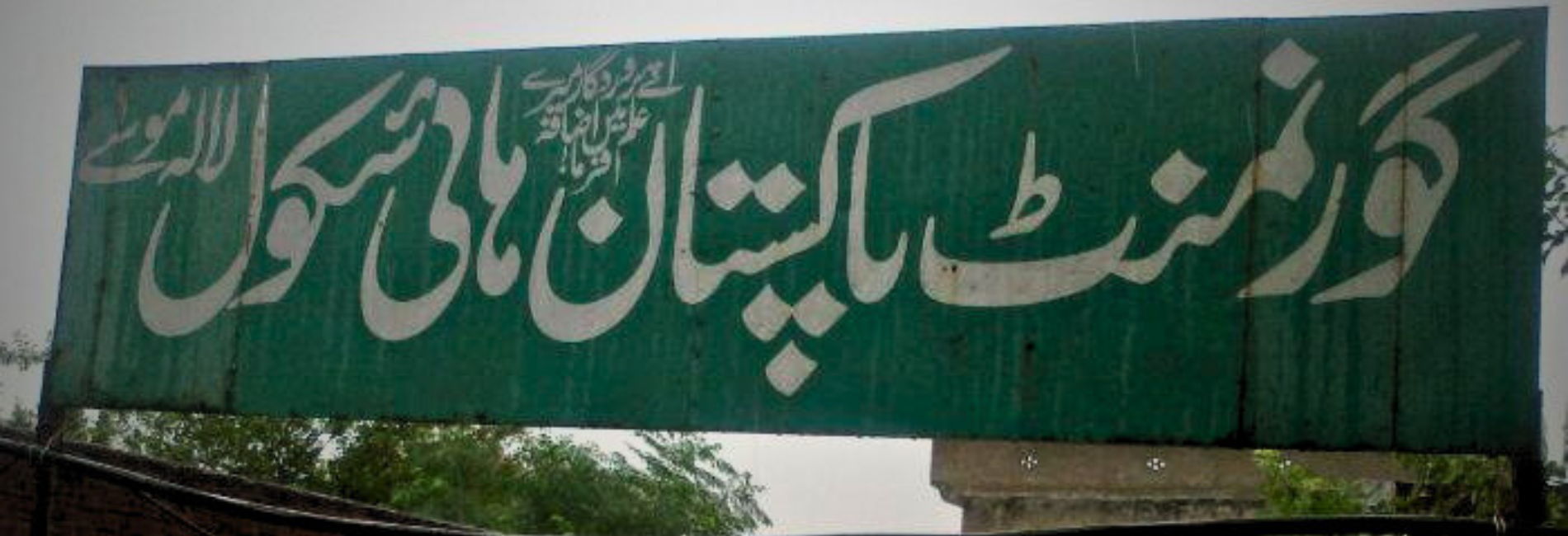

Pakistani Government Schools: A Reflection 40 Years On

Once Upon a Time

There is little research in the Pakistani context on the impact of teacher background on student learning outcomes in government schools. The diversity of teachers across the country is immense, but this post focuses on primary and middle school teachers who entered the teaching service in the late 70s and 80s. In particular, such individuals came from bilingual backgrounds (children of middle-income professional families). Although fluent in both languages – which could have facilitated their employment in exclusively English-medium schools at the time - they chose to teach in government schools to benefit from stable and pensionable careers as a reward for dedicated public service. I will call these teachers ‘early generation’ for the purpose of this post.

When these teachers stepped into their classroom and picked up the chalk and textbook, they did what came naturally to them: they taught their students the way they had been taught as children. In their childhood, these early generation teachers had tended to receive considerable household support to supplement their school education, particularly when it came to reading and writing, spelling, and even English grammar. They had been exposed to an indigenous pedagogy that combined common sense with an understanding of the grammatical structure and syntax of languages prevalent in urban centres of Pakistan - English, and Urdu.

From their first day at a government school, in the role of teachers, they would proceed to do what came naturally to them, recalling the skills their parents used at home, retrieving their pedagogy, and applying them with great effect. The mothers among them had honed their skills in educating their own children. What followed was clear-headed, tried-and-tested classroom teaching practices that introduced English and Urdu to their students, while focusing on comprehension, reading, spelling, and writing skills. They brought to their students the same earnest devotion that their parents had showered upon them as children. In their new role as teachers, they felt the familiar tug of an emotional commitment to education passed down to them. They trusted it. It surfaced as feelings of satisfaction and pleasure, dismay or disappointment at their class’s performance in school - very similar to how they felt about their own children’s progress reports.

At the end of the day, an energizing mixture of parenting and teaching instincts formed the sum total of their personal pedagogy.

Syncing Home and School Values

True teachers take their students’ failures as a serious part of their professional and personal commitment. What matters is where this sentiment comes from and what they do with it. At a deeper level, the early generation teachers’ feelings about their students’ performance had little to do with exams and test preparation, and more to do with a sense of personal responsibility for their students’ learning. Like their parents, they felt both obliged towards, and accountable for, their children’s education – the ones at home, and the ones at school.

Most primary school (female) teachers were socially agnostic. They did not display class-based attitudes and approaches, even if they harboured them. Often their private biases dissolved in their everyday struggle to apply meaningful and adaptive pedagogy. Also, teachers wanted to prove the efficacy of tools that had worked well on them and their own children. There was something else, too: educated teachers knew how defeated they would have felt had their parents treated them as being lesser, or inferior, in any way. “Not to hurt feelings” was their mantra, aware that this natural desire to protect others from emotional injury had significant implications for future learning.

Of course, the math pedagogy was all rote-n-learn. But one can and does learn everything from Urdu, English, the social sciences, to prayers and even the Quran, this way. We all did. Nevertheless, even this berated pedagogy proved to be effective at a time when knowledge and concepts were delivered with understanding, passion, and conviction. By the mid-80s, in Karachi at least, teacher training workshops in teaching the English language and general pedagogy were well underway. Government school teachers benefited a lot from teaching-learning stratagems taken from those sessions. Pedagogy kept getting updated as phonics-based approaches displaced sight-learning for teaching English. This radical shift during the mid-80s in Karachi was pioneered by initial batches of remedial teachers and trainers who introduced the awareness of dyslexia, language learning disabilities, and educational assessments in Pakistan.

Side by side, in the private sector, overseas trainers introduced De Bono’s lateral thinking to crack open fossilized mindsets with out-of-the-box thinking. Multi-sensory pedagogy brought 3-dimensional early childhood learning, requiring manipulatives and educational toys from nurseries upwards to grades 1 and 2. These triggered learners’ curiosity and interest and helped embed basic mathematical and linguistic concepts, via sensory explorations. All during the 80s.

Restoring Before Reforming

Home-learning-&-upbringing experiences have changed devastatingly since then. To disentangle the many causes, will shed little light on the matter at hand, which is this: the quality, the depth, and scope of home-learning experiences of today’s govt. school teachers are a painful, often self-damaging mix of extreme stress, anxiety, economic uncertainty, financial hardships, cultural changes, and little or no real education of the kind needed to support formal school learning. Add to that the priorities of marriage over the pursuit of passion. Young women take to teaching as shoppers take to the parking lot outside the mall. They park their singlehood temporarily and shop for teaching jobs until they get married.

What they often bring into the classroom may be very mangled experiences of childhood learning (if any). Bringing reforms in govt. school education must be preceded by restoring and installing something of value, first, then adding new value subsequently. Our young, well-educated women and men must take up the reins of national education as their grandparents did. It means feeling responsible for our collective future. It will take our finest minds to train our ill-informed but deserving government teachers by modelling basic teaching standards in today’s government schools. Taking inspiration from what and how our educated learned at home, how they teach/taught their own children, might ignite a process of restoration that gets richly embodied in our public culture.

Shad Moarif, President Karislearn Pvt Ltd

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.