Punjab’s Pollution Crisis: Information, Research and Policy Gaps

The authority to regulate pollution in Punjab rests with the provincial Environmental Protection Department (EPD). The EPD has a broad mandate to protect the environment, which includes informing the public on environmental issues and enforcing the Punjab Environmental Quality Standards (PEQS). However, the air quality in major Punjabi cities continues to deteriorate, raising social costs, and jeopardizing economic growth and development.

High Exposure and Costs

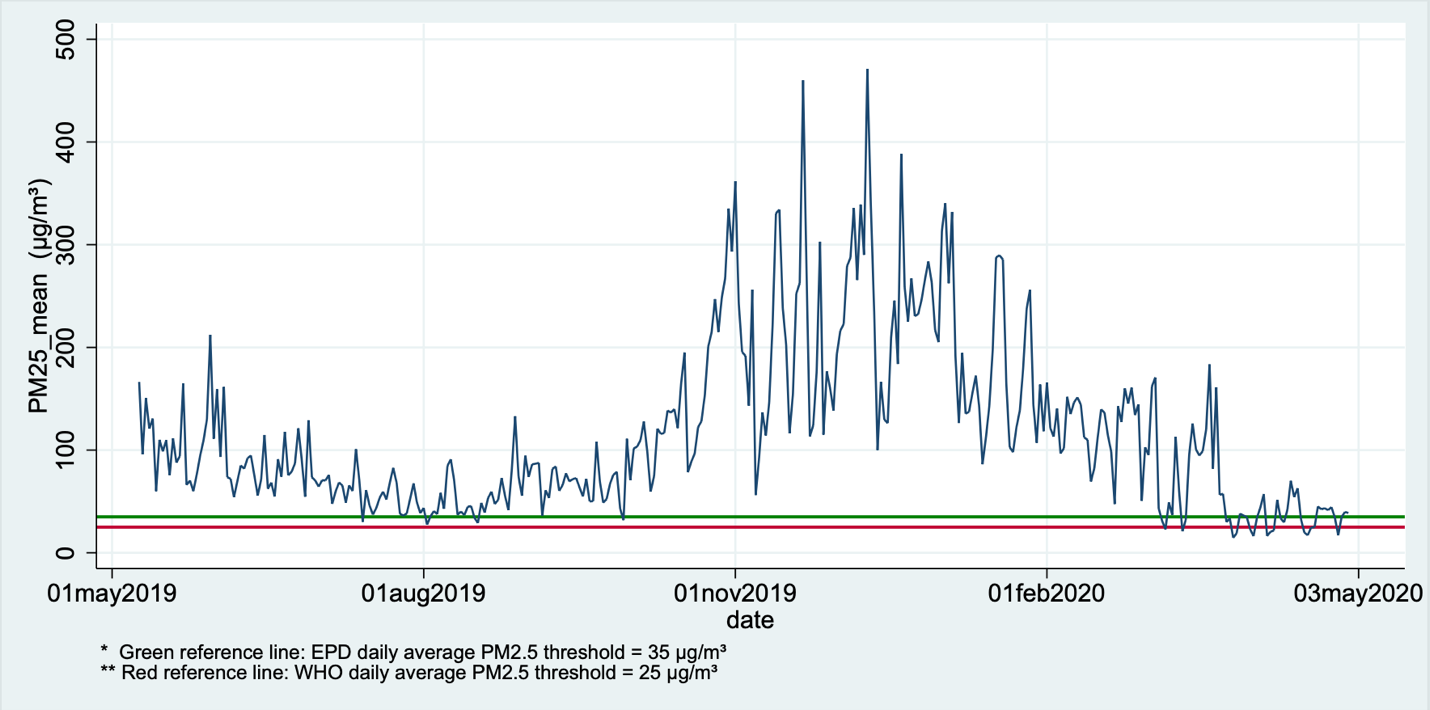

Punjab’s capital, Lahore, consistently ranks as one of the most polluted cities globally. Figure 1 shows the daily trend of Lahore’s average particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) concentration in micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3) from May 2019 – April 2020. PM2.5 comprises fine particles—with a size less than three percent the diameter of a strand of human hair—which easily enter the blood stream when inhaled, posing serious health risks.

Figure 1: Current and Expected Income Changes by Urban/Rural

Source: Data from the US Consulate’s AirNow monitor—some missing values replaced with data from IQAir's private monitors

The trend in Figure 1 reveals that Lahore’s daily average PM2.5 concentration significantly exceeded the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) standard( 25 μg/m3 ) and the EPD’s standard (35 μg/m3 )almost throughout the period. In winter, Lahore experienced daily average concentrations up to 13 times the EDP’s threshold. Lahore’s annual average PM2.5 concentration in this period stood at 117 μg/m3, far higher than the WHO’s standard (10 μg/m3) and the EPD’s standard (15 μg/m3).

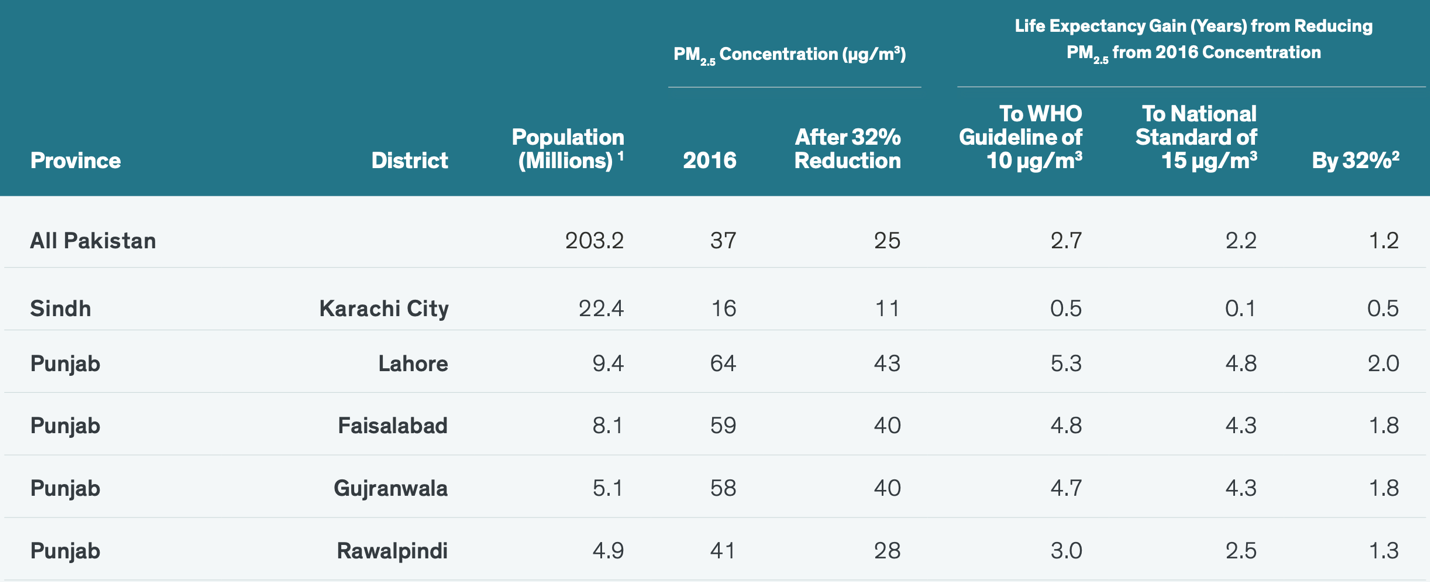

These statistics should alarm citizens and policymakers alike given air pollution carries considerable economic costs. In terms of direct impacts, exposure to polluted air lowers life expectancy and increases infant mortality. If Pakistan continues to sustain its current pollution levels, the harmful exposure will shave off 2.7 years off an average Pakistani’s life—while an average Lahori will lose 5.3 years of their life (Figure 2). Such premature deaths lead to substantial social costs. The OECD estimates that pollution-related premature deaths in 2010 resulted in global welfare loses of $3 trillion. Air pollution also raises the risk of morbidities, including obesity, mental illness, and cognitive dysfunction, further adding to an economy’s health expenditure—in China, such expenditure amounts to over $22 billion annually.

Figure 2: Potential PM2.5 reduction and its impact on life expectancy

Source: Air Quality Life Index, produced by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC)

Beyond increased mortality and morbidity, air pollution carries significant indirect costs. Literature links poor air quality to lower labor supply and productivity, higher incidence of violent crime, and disruptive migration—evidence from China suggests that pollution has driven skilled labor and talent out of important urban centers. Poor air quality also poses risks to the financial sector. Impaired cognitive ability and mood changes because of exposure to polluted air affects investor behavior and can drive substantial variation in the returns on the stock market.

In Pakistan’s case, though some evidence on air pollution-induced mortality exists, studies on its economic cost as well as the welfare losses owing to increased morbidity remain scant. Researchers also have yet to quantify air pollution’s indirect costs to Pakistan’s economy through reduced labor productivity and perverse social behavior. Measuring these costs will prove crucial if Pakistan wants to assess the potential benefits of enacting policies to clean its cities’ air.

Pollution Data and Sources

The dearth of public data on air pollution in Pakistan further compounds the problem. The EPD runs six monitors in Lahore. Many of these monitors frequently remain offline because of power outages or expired data packages. For monitors that function, the EPD reports readings inconsistent with data from private sources—such as the US Consulate’s AirNow monitor. The Department must not only create a vast network of functional monitors in the province and continuously report accurate data, but also consider how to leverage this data to produce valuable and reliable information for the public.

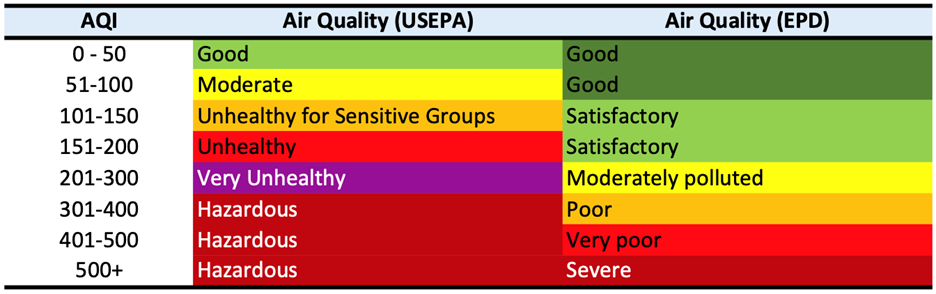

The EPD’s Air Quality Index (AQI)—another measure of air quality which indexes concentrations of several pollutants, including PM2.5—can mislead citizens. The EPD’s AQI excludes an adequate margin of safety, which environmental agencies in many countries build into their indices. For example, the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (USEPA’s) AQI classifies values of 301 and above as “Hazardous”—its highest category; the EPD classifies values between 301 and 400 as “Poor” while its highest category, “Severe,” corresponds to values 500 and above (Figure 3). The EPD must reassess how it constructs its AQI and align it with internationally accepted standards.

Figure 3: Differences in the Air Quality Index advisories

Designing any strategy to reduce air pollution in the province requires the EPD to identify the sources of emissions. Experts usually conduct “source apportionment” studies to ascertain pollution sources. The literature documents only a limited number of source apportionment studies on Punjab. Most of these have become outdated while the recent ones do not apportion PM2.5—the most egregious pollutant.

The suggestive evidence on pollution sources attribute emissions to industries, transport vehicles, brick kilns, stubble-burning in the post-harvest seasons, and transboundary spillovers from India. However, the EPD lacks concrete evidence on the share of each source in total emissions and how these shares vary across time and space. By engaging with researchers, the EPD can gather new and fine-grained evidence on sources with which to better tailor its policies.

Existing Policy

In terms of emissions reduction, the EPD practices what economists label “command-and-control” (CAC) measures. These involve legal instruments—such as mandates, regulations, and standards—monitored and enforced through state authority. For example, through the Punjab Environmental Quality Standards (PEQS)—these comprise seven categories, including Ambient Air, Motor Vehicle Exhaust and Noise, and Industrial Gaseous Emission—the EPD mandates the legally acceptable levels of air quality, water quality, and emissions from various sources.

However, given the EPD’s weak capacity to monitor and enforce standards, polluters receive negligible incentives to reduce emissions. CAC measures also tend to cost society much more than market-based approaches because they almost always apply uniformly to polluters, quashing the incentives of polluters who can reduce emissions more cheaply to pollute less.

Alternative Policies

Incentive-based approaches such as emission charges and tradable permits offer far more flexible and cheaper ways to reduce emissions than CAC measures. Emission charges (also known as emission or pollution taxes) rest on the ‘polluters pay’ principle which states that polluters must pay for the right to emit, thereby compensating users for damaging a commonly shared resource—such as clean air—while creating room for polluters to understand how they can best reduce emissions in their sector. Emission charges also yield revenue for the government, which it can substitute for other taxes or divert to finance other public expenses—the ‘double dividend.’

Emissions trading system constitutes the other popular incentive-based approach to control pollution. Under this system, the regulator achieves reductions by capping emissions at the desired level. It allocates polluters permits defining the limits to which they can pollute—the sum of these limits equals the level at which the regulator set the cap—and allows them to trade the permits in a market.

Implementing an emissions trading system poses challenges for regulators in weak institutional settings. India’s Gujarat State stands out as the first developing region to design an emissions trading program'—the world’s first trading program for particulate matter—in its quest to improve air quality. The results of this program can offer the EPD insights into designing an emissions trading program for Punjab.

Deteriorating air quality will undermine Pakistan’s economic growth. Reducing pollution does not entail quick fixes. Policymakers will have to invest resources in filling research gaps, increasing access to data and information, and designing new policies tailored to the local context.

Sanval Nasim is Assistant Professor of Economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences

Mahnoor Kashif is Senior Research Associate, Department of Economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.