The Pakistani Economy: Can We Grow? | The Friday Economist

The Friday Economist is a collaborative blog series between LUMS MHRC and the CNM Department of Economics at LUMS

Every year, numerous discussions, podcasts, university events, etc. take place regarding the puzzle that is the Pakistani economy. A country endowed with resources like a huge population of approximately 240 million in 2023 (World Population Review) with a budding young labor force, and immense potential for being energy independent by generating solar power consistently finds itself on the brink of economic crisis. Naturally, one can find lots of policy discussions regarding what we do wrong and what needs to be fixed. Unfortunately, these discussions remain just that – discussions. Pakistan has yet to experience a commitment to a long-term, sustainable and meaningful programme for economic stability.

In the #FridayEconomist series, we have previously compared the present Pakistani economy’s position with the Sri Lankan economy (The Pakistani Economy – Another South Asian Default in The Making?), and have discussed major reasons why Pakistan keeps going into crisis mode (Taking Pakistan Out of Economic Crisis: Are We Doing Enough?) with a follow-up discussion on the effect of disastrous floods on the economy (The 2022 Pakistan Floods: Deepening Vulnerability in Society). With that background set, we now aim to discuss the changes we require to grow sustainably.

Before we delve into these changes, we present a quick overview of the Pakistani economy to set the stage. Indicators for two other South Asian economies – India and Bangladesh – are also presented for reference.

The Pakistani economy in South Asia

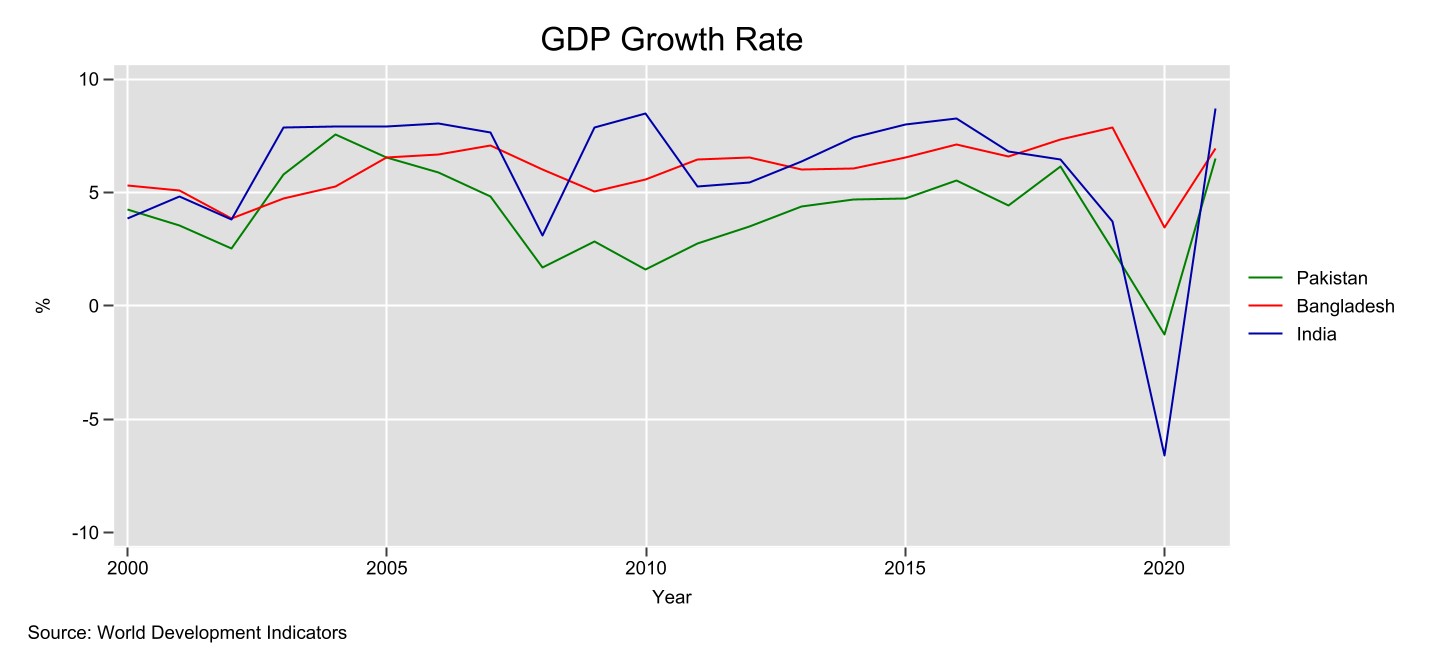

Pakistan’s GDP growth rate is not high enough to meet the growing needs of its expanding population (figure 1a). Over the last twenty years, our economy has been growing at a slower pace than South Asian neighbors, India, and Bangladesh (with a short exception period in 2003 and 2004 where our growth rate was temporarily higher than Bangladesh).

Figure 1a: Comparison of South Asian growth rates, FY 2000/2021

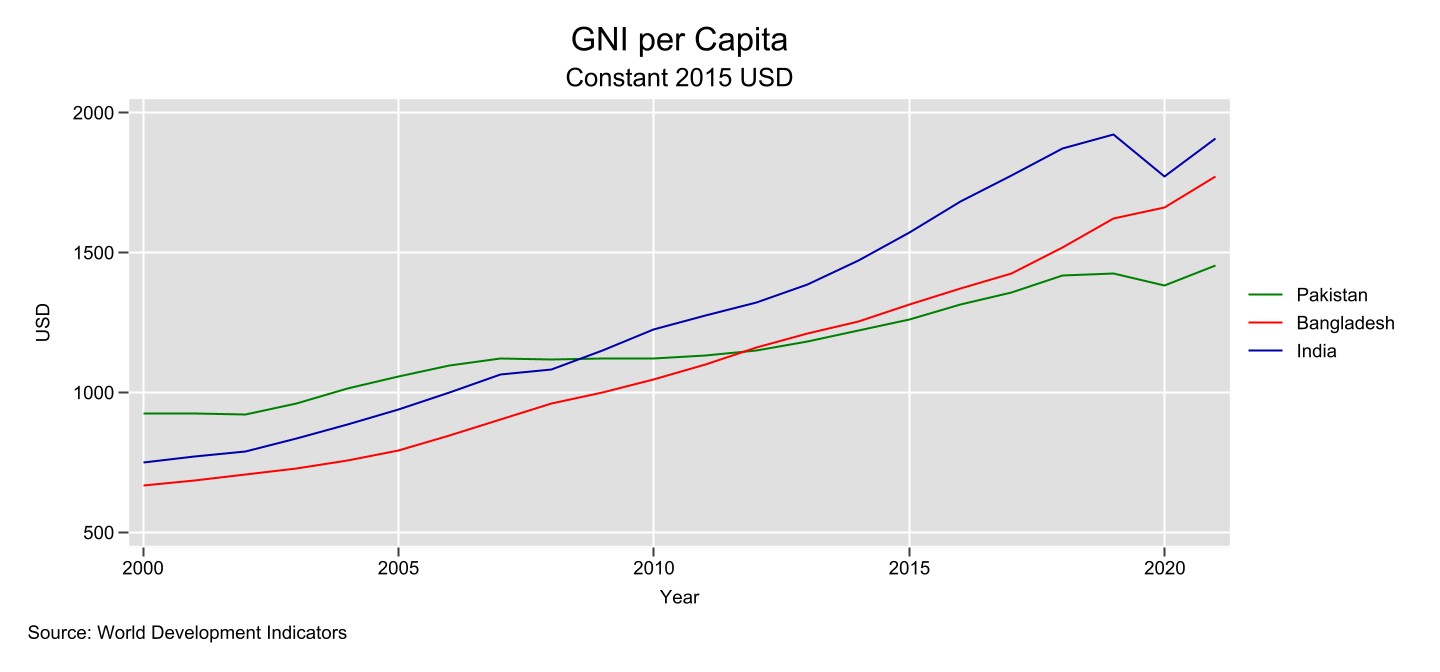

If we look at per capita income, in the last decade, Pakistan’s income per capita has been lower than India and Bangladesh. Figure 1b below shows this trend in Pakistan’s per capita Gross National Income (GNI). In 2021, Pakistan’s GNI per capita was USD 1,455. In the same year, India and Bangladesh had per capita GNI of USD 1,907 and 1,774 respectively (World Bank).

Figure 1b: Comparison of South Asian Gross National Income (GNI), FY 2000/2021

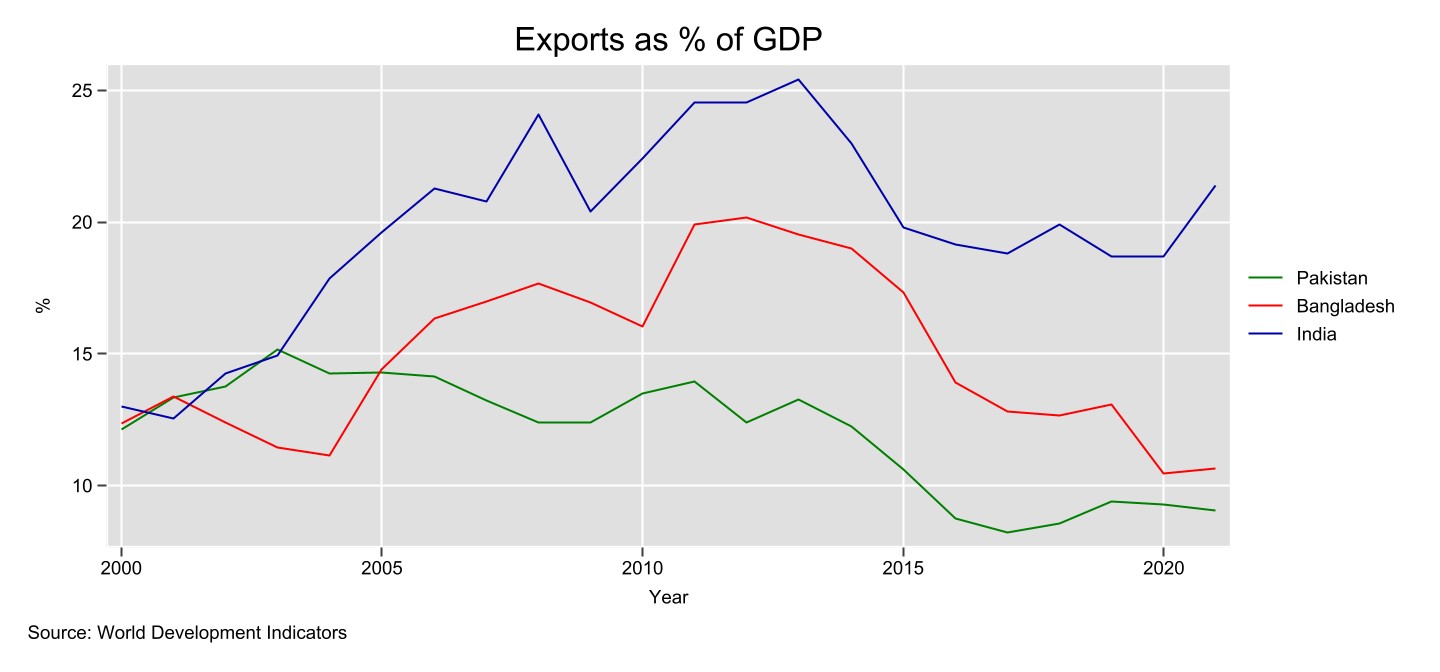

Pakistan’s exports as a percentage of GDP also present a declining trend (Figure 2). Again, they now linger behind Bangladesh and India, whereas in early 2000s the three countries were on a similar trajectory in terms of this indicator.

Figure 2: Comparison of South Asian exports, FY 2000/2021

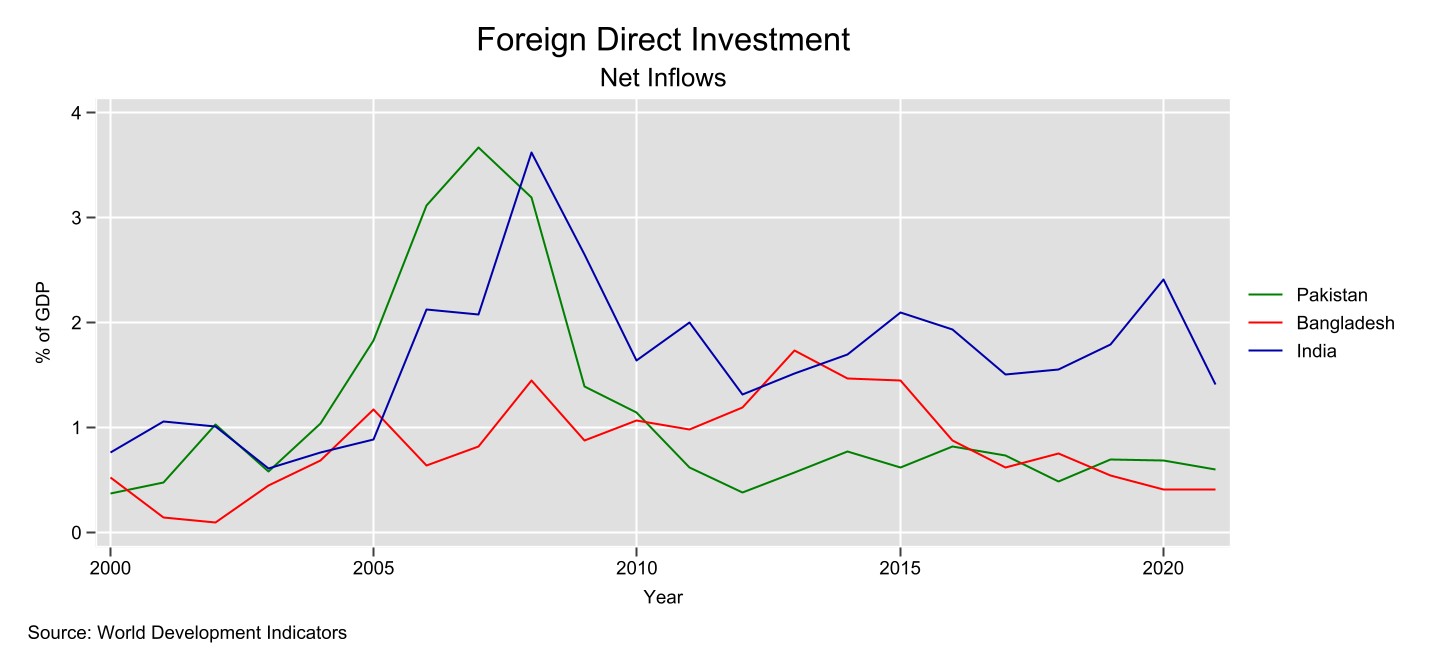

If we look at net foreign direct investment (FDI) into Pakistan, again, a declining trend can be observed over the last decade (Figure 3). Also, Pakistan now lags considerably behind India in attracting FDI.

Figure 3: Comparison of South Asian Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), FY 2000/2021

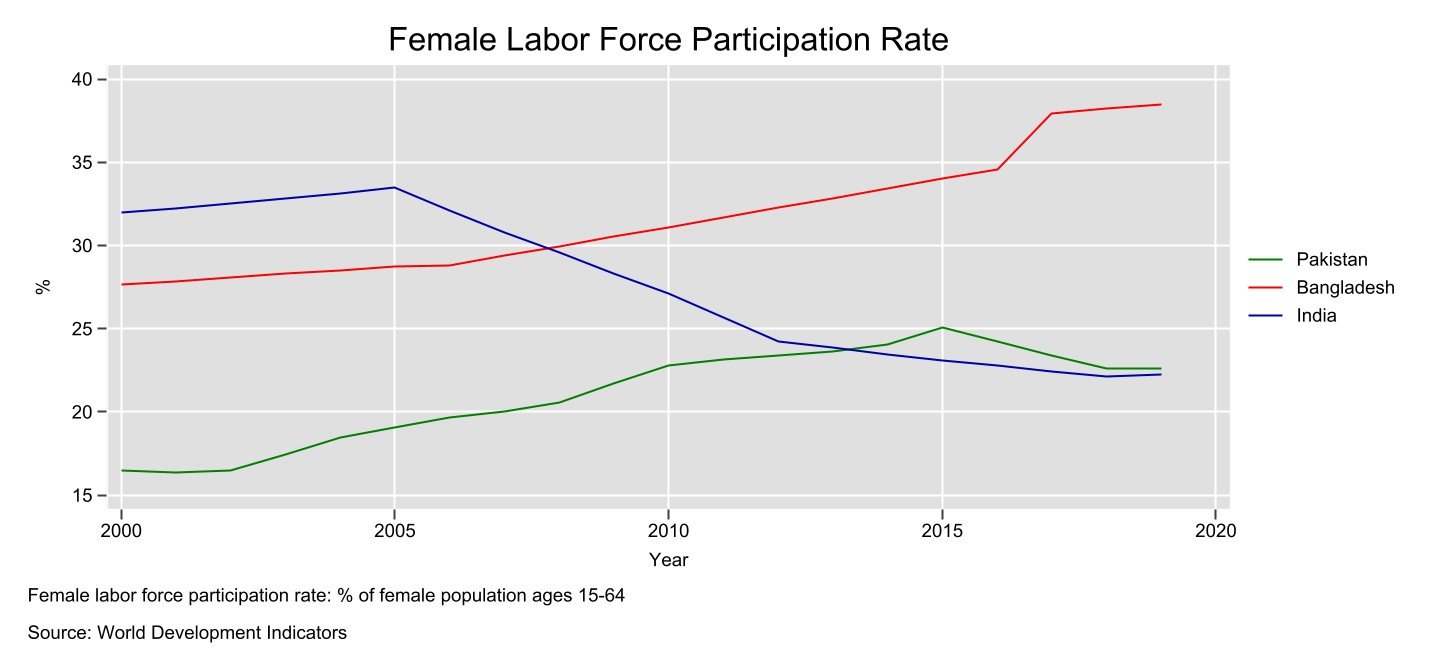

The Pakistani economy also fares poorly in integrating its female population into the labor force and therefore a major part of our working-age population does not join the labor force. In 2019, the female labor force participation rate (percentage of the female working-age population who are in the labor force) was only 22.6%. This rate is comparable with India but far below Bangladesh (figure 4).

Figure 4: Comparison of South Asian Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), FY 2000/2021

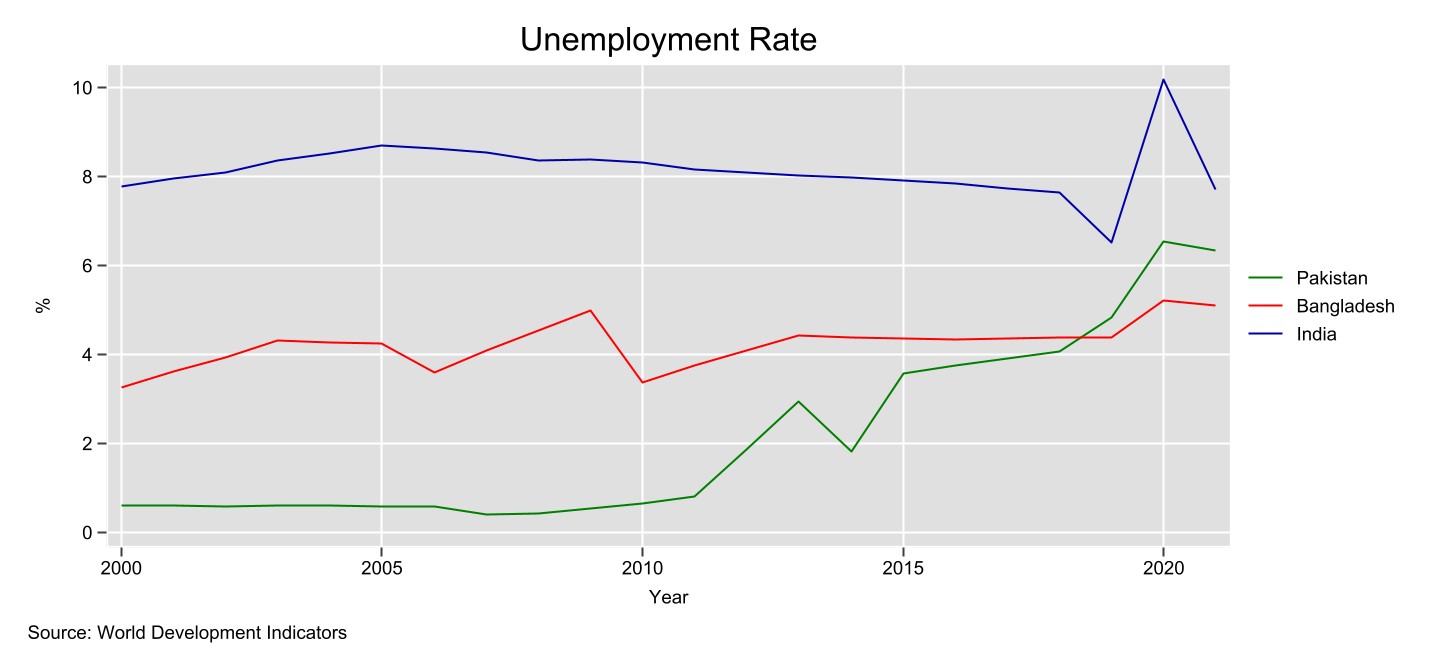

Lastly, the unemployment rate in Pakistan has been on the rise and rose above 6% in 2020, although further investigation would be required to determine how much of this rise is attributable to Covid-19 economic effects (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Comparison of South Asian unemployment rates, FY 2000/2021

Other than these, Pakistan also faces double-digit inflation which has substantially raised the cost of living in the country; depleting foreign exchange reserves; rising debt; and an incessant energy crisis. The country keeps running into macroeconomic crises by running large fiscal and current account (CA) deficits.

As the graphs above have shown, the Pakistani economy struggles with optimistic growth prospects. This is likely to further income inequality in the country, an economic health indicator most commonly expressed through a Gini Coefficient (here’s an easy definition of this), which is at 0 for perfect income equality in a country, and 100 for perfect income inequality. Pakistan’s Gini Coefficient’s value, most recently measured in 2018, was 68.4 - higher than Bangladesh (67.6), Nepal (67.2), Sri Lanka (60.7), or even India (64.3) for the same year (World Economics). The current economic crises faced by Pakistan, coupled with inefficient productive policies, are likely to pose serious challenges to the growth trajectory (hence income distribution) of the country, deepening Pakistani’s vulnerabilities and frequently bringing the economy closer to the brink of collapse.

What needs to change: signal productivity in new sectors

The Pakistani economy has historically focused on sectors that lack a global competitive edge. The automotive industry example fits well here. This industry has enjoyed long-term protection, but we have been unable to develop an auto sector that can sustain itself without protection, let alone export cars. Another big one is real estate, in which inefficient capital tax structures incentivize investment and protection, shifting market resources and public will away from investing in other more productive sectors (that can grow faster and directly boost the country’s export portfolio).

Similarly, agriculture taxing within Pakistan also needs sensible revisions. the sector also suffers from a highly polarized tax incidence (IMF). This remains of the most contentious areas that the country has struggled with since the 1970’s; however, if Pakistan has to grow, reform to this sector are instrumental.

To emerge from this vicious cycle of focusing on unproductive sectors, the government needs to identify and shortlist productive sectors with export potential and create a positive environment which encourages investment in them.

There are many areas with probable scope of success for Pakistan’s economy. These include Pakistan’s energy and resource sector, value-addition agriculture and mid- to high-value niche manufacturing (e.g. specialized surgical and sporting goods or mineral/gem-based technologies). Holistically speaking, the government needs to incentivize the development of these sectors. As productive sectors grow, they are also more likely to reduce unemployment with accelerated job creation.

But a key sector to continue investing in is technology, an area that has seen one of Pakistan’s fastest export growth rate – slowed down only by a struggling FOREX (foreign exchange) position for Pakistan. PASHA (Pakistan’s leading software houses association for IT and ITES) reports that amid the increase in Pakistan’s trade deficit, technology was the only sector that experienced a trade surplus of an astounding 75% in the year 2022/23.

What needs to change: re-energize

A major component of Pakistan’s import bill are oil imports. In Fiscal Year 21/22, petroleum products constituted some 23% of Pakistan’s total imports (State Bank of Pakistan). To meet a growing economy’s energy needs, this is an import that cannot be curtailed. This problem plays an important role in the country’s worsening CA. So, it is critical for Pakistan to reassess its energy situation and look for alternative locally available energy sources.

One such source is solar power, which Pakistan has abundant potential to generate. Pakistan’s geographical location and climate favors the adoption of solar power- a cheaper alternative to the conventional energy resources it relies upon. According to a recent World Bank study, utilizing only 0.071 percent of Pakistan’s land for solar power would meet its current electricity demand. Solar power use would be not just cleaner, renewable and more cost-effective, it may as well carve a path for Pakistan out of circular debt.

Despite its huge potential for energy and manufacturing needs, solar programming often encounters an investment reluctance driven by a fear of high generation and maintenance costs. Three key challenges identified as barriers to the development of solar power plants in Pakistan include tariff uncertainty, land identification, and pre-planned transmission mechanisms. As a consequence of these challenges, there has been limited penetration of distributed solar energy solutions in the country’s residential and commercial sectors.

Other renewable energy options include investments in hydel or wind power which have been slow in their entries as cheaper alternative energy sources despite government efforts. For instance, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) launched a subsidized financing scheme to offer financing to renewable projects at a subsidized interest rate of 6 percent per annum. According to the Asian Development Bank, this intervention has attracted commercial entities more effectively than individuals. The report also proposes three solutions to increase effectiveness of such green energy schemes.

One solution could be for the State Bank to extend financial provision to energy distribution and supplier entities rather than buyers in a bid to make renewable energy products more affordable. Another proposed recommendation to mitigate the risk of loan default is to enable at-source deduction from salary accounts of buyers. Lastly, SBP could introduce Islamic versions of its conventional subsidized financing schemes to encourage the financing and adoption of distributed energy solutions among Islamic investors to gain mass interest.

What needs to change: redistribute wealth

If the discussion and numbers above are any indication to go by, Pakistan’s economy is on a losing trajectory. But not everyone in the country suffers; and those who do, do not suffer equitably. At a minimum, people within the Pakistani economy in its current state are rapidly falling into two distinct categories – winners and losers.

Winners are those groups who benefit from the status quo, and whose members maintain enough wealth or income to sustain their existing purchasing power. They are typically members of elite or upper middle classes of the economy; they may also be middle-class families with educated members employed in high-value jobs abroad on whose remittances domestic households are run. The rest of Pakistan is increasingly missing out on economic opportunity, savings or sustainable growth. One indication of this alarming reality is the 8.5% unemployment predicted for FY 2024.

Notwithstanding the multiple reasons that have emerged over FY 22/23 for Pakistan’s deteriorating economic health, a key structural reason we stand where we do is the unproductive nature of economic activity of some of Pakistan’s largest wealth segments i.e. accumulated gains are frequently invested in unproductive sectors like real estate. Real estate activities contributed to 9.6% shares in services and 5.6% share in GDP for the year 2021/22. But the issue here is not so much the existence of a polarized class structure within Pakistan as it is the evolution of an unproductive market structure that accompanies this class structure.

To bring meaningful change, those who are already winning need to be incentivized to invest in productive sectors within the economy. One way could be the revision of asset/land taxation structures to discourage locking precious monetary resource into unproductive land investments (speculative; those that are not actively for residential or commercial construction and use).

These are just a few main ways in which we propose rethinking the Pakistani economy. The key assumption here remains working towards a system that seeks to bridge income inequalities. Without this will, many of these policies may also end up reinforcing an extractive status quo!

Rabia Khan, Teaching Fellow, Department of Economics, LUMS

Verda Arif, Teaching Fellow, Department of Economics, LUMS

The writers acknowledge Dr Atif Mian, Professor of Economics, Public Policy and Finance at Princeton University and Dr Ahmed Jamal Pirzada, Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Bristol for their views and recommendations for Pakistan’s macroeconomy.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.