The 2022 Pakistan Floods: Deepening Vulnerability in Society | Friday Economist

The Friday Economist is a collaborative blog series between LUMS MHRC and the Department of Economics

According to the Global Climate Risk Index (2021), Pakistan is ranked as the eighth country in the world most vulnerable to long-term climate risk. The country has experienced extreme weather events in the past and continues to do so. In 2010, Pakistan’s national floods affected more than 20 million people and damaged over 20 percent of the land area (Government of Pakistan).

But the 2022 floods did even worse. This year, national rainfall for the month of July was significantly (by 180%) above the average and stood as the record wettest July since 1961 (Pakistan Meteorological Department). Torrential rains coupled with riverine, urban and flash flooding led to an unprecedented disaster in Pakistan that caught the country off guard. In addition, continued economic and political crises compromise the country’s ability to address the persisting climate fallout, worsening the humanitarian crisis.

In light of recent adversity, this blog piece aims to address two main concerns. Firstly, how has this natural calamity affected women and children, two of the most vulnerable groups of Pakistani society? Secondly, to what extent can economic and political factors be held accountable for the exacerbation of the situation?

The scale of wreckage from the recent monsoon season

Figure 1 below, a satellite image from NASA, indicates the extent of rainfall that led to flooding within a few weeks. The worst flooding occurred along the Indus River in the provinces of Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan, and Sindh, washing away about 150 bridges and destroying 3,500km of roads (NASA earth observatory).

Figure 1: Extent of flood evolution on August 4 (left) and August 28 (right), 2022

Source: NASA earth observatory

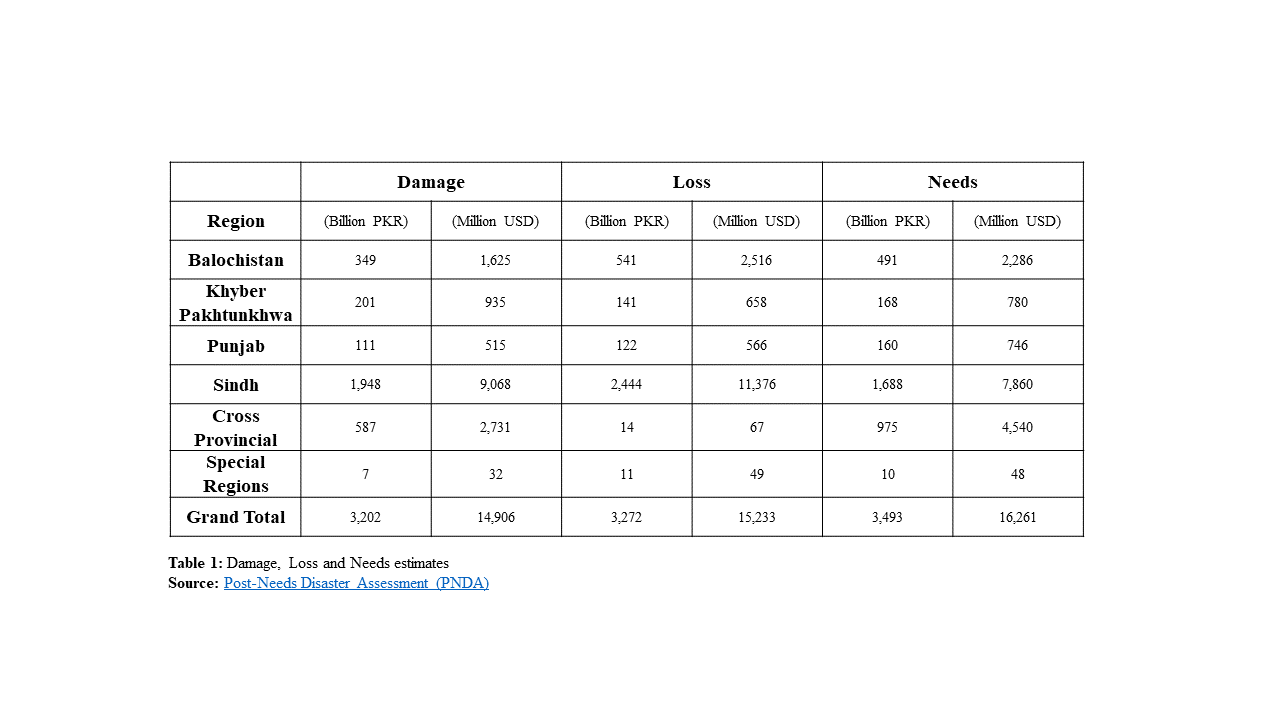

Table 1 below gives a region-wise estimate of the damages. According to Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA), the total damages are around PKR 3.2 trillion (USD 14.9 billion), the total loss at PKR 3.3 trillion (USD 15.2 billion), and the total needs at PKR 3.5 trillion (USD 16.3 billion). Additionally, the top three sectors suffering the most damage are housing at PKR 1.2 trillion (USD 5.6 billion); agriculture, food, livestock, and fisheries at PKR 800 billion (USD 3.7 billion); and transport and communications at PKR 701 billion (USD 3.3 billion).

A parallel comparison of the above statistics with the statistics from 2010 floods can help to gauge the severity of this year’s flooding disaster. Compared to this year, direct damage caused by the 2010 floods was estimated at PKR 552 billion (USD 6.5 billion) while indirect losses amounted to PKR 303 billion (USD 3.6 billion). The agriculture, livestock and fisheries sector suffered the highest damages, calculated at PKR 429 billion (USD 5.0 billion), thus suggesting that the effects of this year’s flooding are manifold compared to those of the year 2010 (Government of Pakistan).

Additionally, damages at the micro level are approximated to be around 33 million people; that is, 1/7 have been affected by the floods, with nearly 8 million displaced. The floods took the lives of more than 1,700 people, one-third of which were children (The World Bank).

Impact on already marginalized segments of society

Women in Pakistan contribute to nearly 68 percent of the labor force in the agriculture sector (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics). While the statistics in Table 1 above, estimating damage to the agriculture sector, indicate a higher vulnerability of women to climate change, the extent of this vulnerability is augmented further by the deep-rooted gender inequalities that frame the country’s economic and social fabric. According to the 2022’s World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index report, Pakistan ranks as the second worst country in the world in terms of gender parity. Additionally, a staggering 28% percent of women have experienced physical violence in Pakistan and 34 percent of ever-married women have suffered from spousal abuse at some point in their life (The Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-2018). Against this backdrop, natural disasters, like floods, will further reinforce existing gender inequalities by adding to the woes of millions of women and young girls, who are constantly fighting for their rights to adequate education, health, and economic opportunities, while operating within a primarily male-dominated society.

The 2022 floods damaged 13% of health facilities, which interrupted health service delivery from the community level (primary healthcare including Rural Health Centers and Basic Health Units) through the secondary level (Tehsil and District Headquarters as well as Civil Hospitals). More than 1/5th of affected facilities were fully damaged (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)). Mounting health-related needs and inadequate healthcare systems present a serious issue. There are almost 650,000 pregnant women in Pakistan’s flood-affected areas, with up to 73,000 estimated to have been giving birth just before the floods hit (United Nations). This suggests a stark shortfall in the likely pre- and post-natal care that these women will likely have received, along with an absence of skilled attendants at births. As the numbers become more certain, all of this will likely further aggravate Pakistan’s already poor performance in terms of maternal mortality ratio, infant mortality rates and under-5 mortality rates, which are among the lowest in the region (The World Bank).

In addition, the catastrophic floods have already claimed the lives of 615 children. Almost 10 million children require immediate lifesaving support (UNICEF). What makes matters worse is that child nutrition is already a pressing issue in Pakistan. For instance, Sindh is the worst-hit province in Pakistan in terms of malnutrition and food insecurity, with a prevalence of 49.9% for stunting, 16.1% for wasting and 4.4% for severe wasting (UNICEF). Flood-stricken areas have a very high prevalence of diseases like diarrhea, malaria, dengue, cold, and skin diseases (Government of Pakistan). Lack of access to healthcare services and crowding compound the risk of death of children, particularly ones most vulnerable to these infections with an already compromised health status.

The extent of Pakistan’s economic and political crises on the efforts to tackle climate challenges

Economic crises

With recent economic crises compelling Pakistan to request IMF loan assistance, the country finds itself in an already precarious situation. Factors like a low tax-to-GDP ratio, consistently large trade deficit, high debt-to-GDP ratio and lack of foreign reserves have left Pakistan in a deteriorating state on the macro level. Huge finances are required to rebuild the damages caused by the flood, and a large chunk of these finances will inevitably have to come from international sources. However, with an already weakened economic state, the risks of collapse and government failure are high. In order to regain credible access to global financial assistance, the country will have to actively pursue economic reforms. Inevitably, rehabilitation and recovery will have to happen with a heavy reliance on loans that help mitigate climate-related damage.

Political schism

Pakistan is a heavily divided country when it comes to political matters. Extensive print and electronic media coverage of an ongoing leadership contest between the Pakistani government and its opposition parties significantly diverts mainstream attention away from the persisting effects of this year’s floods. Could such political contests be the reason Pakistan lagged in timely evacuations and subsequent disaster management, especially in high alert areas, despite receiving warnings from the Meteorological Department (Pakistan Meteorological Department)? Against this high-tension political backdrop, what else does Pakistan’s current flood response reveal about the attention paid to planning instruments of state, such as the Disaster Management Plan devised following the 2005 earthquake and 2010 floods (National Disaster Management Authority)?

Pakistan’s preparation for future climate change encounters

The impact of the floods will be felt in Pakistan for a long time — in the loss of infrastructure, agriculture and livestock, and in the implications for health and nutrition. Nevertheless, the tragedy is an eye-opener as to how vulnerable groups in society often end up bearing the lion’s share of the burden. Women and children are most susceptible to the impacts of climate change, as argued above. Thus, there is a dire need to make them the focal point of climate change adaptation and mitigation policies.

Secondly, questions raised around government ability to act rapidly on precautionary measures upon receiving early warnings need more effective answers. Although some of this year’s flooding may not have been predictable using current data, tools, or policies (such as flash floods in Gilgit Baltistan or cloudbursts in the Suleiman Range), most of this year’s devastation draws urgent attention to a Pakistani political economy that facilitates a lazy response to climate emergencies in one of the world’s most climate-disaster vulnerable geographies.

Verda Arif is a Teaching Fellow at the Department of Economics, LUMS

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.