Can Light-touch Motivational Nudges Motivate Women to Enter the Workforce?

Female labour force participation (FLFP) is low in Pakistan; at 22%, it is less than a third of the male labour force participation and lower than participation rates in other South Asian countries (Bangladesh, 36%; Sri Lanka, 35%; Nepal, 83%) (World Bank, 2020). The gender gap in economic participation is not explained by disparity in the education market; almost half the students at intermediate, graduate, and postgraduate level in Punjab are women (Punjab Development Statistics, 2018). Do women simply lack the desire to work? We conducted in-depth focus group discussions (100 in all) followed by interviews (2500 in all) with female undergraduate students in public colleges in Lahore, which suggest the opposite: 4 out of 5 interviewed women expressed a desire to work after graduation and nearly half expressed a desire to work within 3 to 5 years of graduating (Ahmed et al., 2020). In fact, 1 in 5 women reported combining part-time work with their studies, with a large majority earning PKR 10,000 or less on a monthly basis. This points to a puzzle: why aren’t much higher levels of women entering the labour market given these levels of aspiration in the population.

Addressing this puzzle is important because increasing the economic participation of educated women can be a major catalyst for development in Pakistan. Increasing women’s economic participation provides an opportunity to harness the huge potential of the demographic transition and address gender inequality. In Punjab alone, one half of its 110 million population is female, and one third of them fall in the 15-29 years age bracket. Timely investments in female youth at this critical age can make them an asset for the country, with the potential to accelerate economic growth (Pakistan Jobs Diagnostic, 2017). Economically empowering young women can also have positive spillover effects on Pakistan’s key social indictors. Studies in several developing country contexts have shown that spending on child education and nutrition increases when women are principal recipients of monetary resources (Lundberg, 1996; Duflo, 2003; Rawlings and Rubio, 2005; Handa and Davis, 2006, Pitt et al., 2006).

Existing work highlights external constraints and internal barriers which make it difficult for women to transition to the labour market. Transport, social norms, household dynamics, and access to job opportunities have been found to be significant barriers which keep women from being gainfully employed (Field et al., 2010; Heath and Mobarak, 2015; Field and Vyborny, 2016; Erten and Keskin, 2018; Jayachandran, 2020). Internal barriers, in the form of lack of same-gender role models, mentors and peer support are also important determinants of labor market outcomes for women (Riise et al., 2020), though they have received less attention in literature (McKelway, 2020). Role models and mentors, in particular, can reduce the ‘stereotype threat’ and increase participation by motivating women to their aspiration to work (Kofoed and McGovney, 2017; Breda et al., 2018; Mansour et al., 2018; Porter and Serra, 2020; Lopez-Pena, 2020).

Our Setting

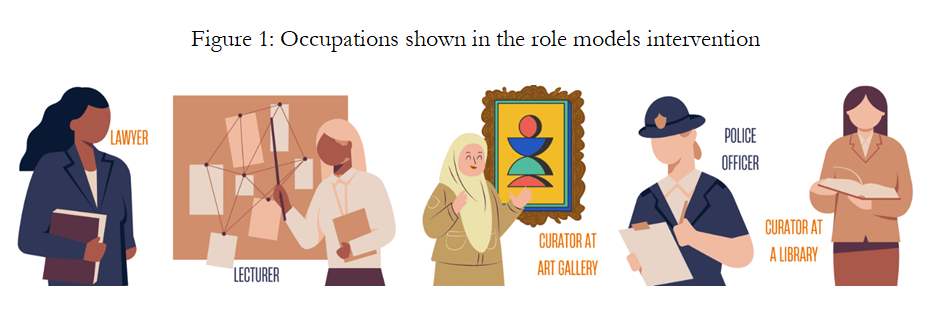

In this paper, we test if a low-cost, motivational nudge in the form of stories of female role models can encourage female graduates from to increase labor force participation. We conducted a randomised control trial with 2500 female undergraduate students in 28 female only public colleges in Lahore, Pakistan. We alleviated some of the external constraints by giving the entire sample information about Job Asaan, a job search portal that also provides support with CV making and interview preparation. Half of the sample was then individually and randomly selected to watch a 10 minute video showcasing real-world female role models, gainfully employed and from a similar socio-economic group as the students, followed by a brief discussion with the enumerator on the key messages of the video. The role models in the video belonged to a diverse set of professions that young undergraduates typically aspirt to – they include a lawyer, a curator at library, a lecturer at a public university, an assistant curator at an art gallery and a police officer. The role models in the video encouraged a growth-mindset in the students and motivated them and embodying a ‘representation of the possible’ (Porter and Serra, 2020). The other half of the sample students formed the placebo group and watched a video of a similar length on a topic.

We collected high frequency data on job search efforts and outcomes, conducting 3 follow-up surveys over a period of 18 months after the intervention. The 18 month followup was a phone survey conducted right after the COVID-19 induced lockdown in March 2020 where we collected information both about the situation before the lockdown in February and after it in May 2020, i.e. 15 and 18 months after the intervention, respectively.

Key Findings

The role model intervention led to a higher growth mindset among treated students (Blackwell et al., 2007) i.e. a belief that they can be successful in their goals through effort, hard-work and dedication. Treated students also scored higher on an ‘absorption’ index (Banerjee et al., 2019) i.e. they were significantly more engaged with the video, reporting that it captured their attention, touched them emotionally, and inspired them to learn more about the characters shown in the video. Given the relatively short duration of this initial interaction, we reinforced the key messages of the video three months after the intervention. Treated students remembered the names and occupations of role-models before this reinforcement at three months, and in surveys conducted eighteen months after first watching the video.

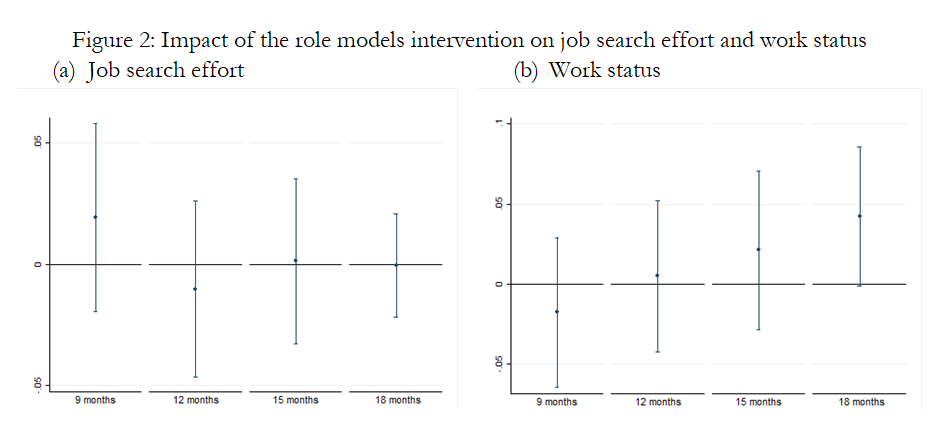

In the short run, we do not find a significant effect of the role-model intervention on job search or the likelihood of working (Figure 2). However, over a longer period of time (at 18 months after the intervention), women in the treatment group are 4.7 percentage points more likely to be working (Figure 2, panel b), which is 24% higher than the placebo mean of 20.1%. Among these treated women, who were not working at 12 months (after the intervention) but report working at 18 months, 62% are tutors - of which (79%) provide tuition from home earning on average USD 36.4. A fifth (20%) are employed in other, full time salaried work earning a higher salary of USD 81.35, 16% are working part-time and a small proportion (2%) are self-employed, providing beauty, stitching or embroidery services. They earn an average income of USD 55.56.

Note: This figure displays treatment effect coefficients from an OLS regression run separately for each survey round. 9, 12, 15 and 18 months refer to the number of months since the baseline and intervention when the dependent variable was measured. The dependent variable ‘Job search effort’ in panel (a) is a binary indicator equal to 1 if the woman looked for work in the last month. The dependent variable ‘Work status’ in panel (b) is a binary indicator equal to 1 if the woman in engaged in any type of work, whether full or part time. The coefficients shown are for the ‘treated’ variable which is a binary indicator equal to one for respondents who viewed the role model video; 0 for those who viewed the placebo video.

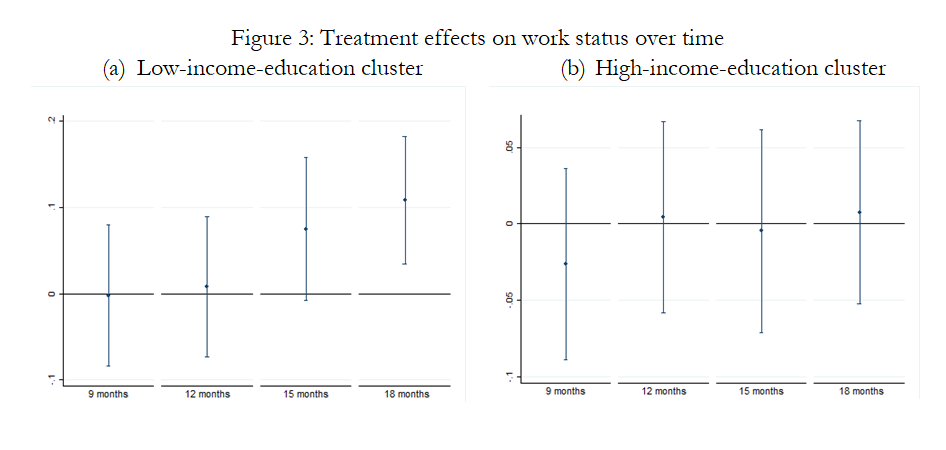

We explore whether the long-run treatment effect is found in women from both low-income (LI) and high-income (HI) backgrounds. Students in the LI(HI) group report an average monthly income of 262(356) USD, 6(12) completed years of father's education and 3 (11) completed years of mother’s education. We find that the average treatment effect at 18 months is driven by an effect of 11% points in LI respondents while we find no differences in the likelihood of working in the HI sub-sample (Figure 3). These heterogenous effects are not surprising given the LI group is much more likely to report adverse outcomes for their primary male earner as a result of the COVID19 pandemic.

Note: This figure displays treatment effect coefficients from an OLS regression run separately for each survey round. 9, 12, 15 and 18 months refer to the number of months since the baseline and intervention when the dependent variable was measured. The dependent variable ‘Work status’ is a binary indicator equal to 1 if the woman in engaged in any type of work, whether full or part time. The coefficients shown are for the ‘treated’ variable which is a binary indicator equal to one for respondents who viewed the role model video; 0 for those who viewed the placebo video. Panel a reports results for the low-income-education sample and panel b for the high-income-education cluster sample.

To summarize, we observe significant effects of the role model intervention women’s labor market behavior at 18 months after the intervention. These effects are primarily driven by women from low income households. Our findings highlight the potential of using a low-cost light-touch intervention in increasing participation of women from the poor and vulnerable segments of society. However, the lack of average treatment effects among women from higher income households shows that improving participation in the overall population of women will require dealing with structural constraints such as safe transportation options and that without such complementary initiatives, light-touch interventions may not provide sufficient motivation for women to enter the labor force.

Hamna Ahmed is an Assistant Professor at Lahore School of Economics and a Senior Research Fellow at Centre for Research in Economics and Business (CREB)

Mahreen Mahmud is an Assistant Professor at University of Exeter

Zunia Saif Tirmazee is an Assistant Professor at Lahore School of Economics and a Senior Research Fellow at Centre for Research in Economics and Business (CREB)

Farah Said is an Assistant Professor (Economics) at LUMS and Associate Director MHRC.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.