Career or Children? The Unfair Choice Facing Working Mothers

In 2023, Pakistan’s female labor force participation was 24%, with less than 10% participation in the formal sector. In Pakistani society, men are typically the primary breadwinners in a household, so women are often expected to leave or take a break from their careers after giving birth. However, the challenges do not end there. Even the women who choose to remain in the workforce after motherhood encounter penalties at work, a phenomenon commonly known as the “motherhood penalty” in the labor economics literature.

According to PWC’s Women in Work Index report (2023), motherhood penalty results in the loss of lifetime earnings experienced by mothers. In six OECD countries, this penalty was observed directly as a 60% drop in earnings for mothers, compared to fathers, in the 10 years after the birth of the first child. This penalty is due to underemployment and slower career progression after having a child. If women decide to take a career break, it can hinder their chances in securing a job in the formal sector. As a result, they might have to change their career path and start from scratch. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research reports a 30% drop in the earnings for women who stay out of the workforce for two to three years. Extensive academic research has documented that many women either leave the workforce or shift to part-time roles following the birth of their first child (Berniell et al, 2024; Anders, 2004).

A Harvard study from the U.S. found that mothers received competency ratings 10% lower than equally qualified non-mothers. Perhaps most strikingly, mothers were six times less likely to be recommended for hiring, and if hired, were offered starting salaries 7.9% lower than non-mothers. One possible reason for this difference is manager perception regarding commitment to careers. Yet, the same study reported that while mothers were perceived as “12.1 percentage points less committed to their jobs than non-mothers”, fathers were seen as “5 percentage points more committed than non-fathers”. Clearly there is a marked gendered element to this “penalty”.

A study published in the Journal of Labor Economics (Angelov, Johansson, & Lindahl, 2016) found that in Sweden, the male-female income gap between working parents widened by 32 percentage points fifteen years after the birth of their first child . Similarly, a recent paper in Oxford Economic Papers (Doris, O’Neill, & Olive Sweetman, 2025) showed that although male and female Irish graduates earn similarly at the start of their careers, a significant wage gap emerges after ten years of their graduation. While the primary reason for that was a 24% decline in mothers’ earnings relative to their pre-motherhood earnings trajectory, the labor literature that suggests that in stark contrast to their female counterparts, men receive a dividend on becoming fathers.

Together, these findings point to a pervasive motherhood penalty – a pattern of disadvantage where mothers are financially penalized, viewed as less competent, discriminated against, and sidelined. Their entire career trajectory can be altered, while fathers often benefit from what seems to be a “fatherhood premium,” perhaps reflecting assumptions that men are the primary breadwinners.

In this blog, we examine how the motherhood penalty can be traced through trends in labor market outcomes. We then draw on firsthand accounts to explore the unique challenges faced by working mothers at a private sector university in Lahore.

Tracing the Drop: Mothers and Labor Force Outcomes

The greater reproductive burdens faced by mothers, have been linked in the literature, with choice of women’s occupations, interruptions in career trajectories, and with labor force exit. According to the PSLM surveys, 44 percent of mothers give “too busy doing domestic work” as reason to not work, whereas only 19.5 percent of non-mothers do so (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Calculations based on PSLM rounds of 1998-99, 2001-02, 2005-06, 2007-08, 2011-12 and 2013-14.

Indeed, estimates from the Pakistan Labor Force Survey (LFS) show a reduction in Labor Force Participation (LFP) of more than 1 percentage point (which is a meaningful drop considering low female LFP in Pakistan – 24% in 2024) with the birth of the first child. Yet, the number of children is not the only factor that matters for mothers’ LFP rates, the age of the child also matters. Here, participation rates tend to be the lowest for women with children under 5 years of age, indicating that burdens tend to be highest here. Interestingly, for women with older children, participation rates tend to be even higher than those with no children, possibly because of rising costs requiring an additional income stream (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Source: Calculations based on LFS 1990-91 to 2014-15.

Note: Mean age of women provided in parentheses.

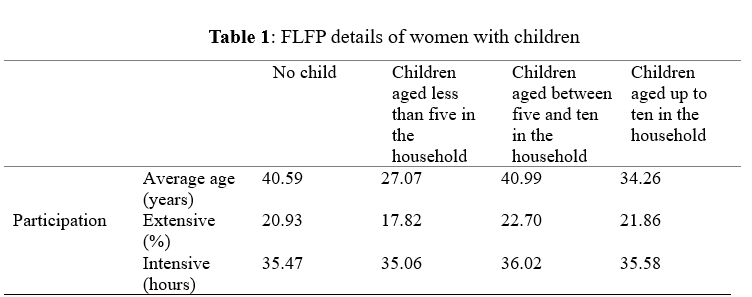

It is worth noting here though, that while participation rates (at the extensive margin) tend to be significantly lower (at the ten percent level) for women with children below the age of five, than those with either no children or children that are older, the difference at the intensive margin (i.e. in terms of hours worked) is minimal (Table 1). Hence, while women with younger children are entering the labor market at lower rates than those with lower reproductive burdens, once they are in the labor market, they tend to work similar hours. However, it is worth noting that regardless of the presence of and age of children, women’s work remains in the part-time category at 35 hours per week per the LFS, unlike that for men which hits the full-time category i.e. 51 hours per week.

Source: Author’s calculations based on LFS 1990-91 to 2014-15.

Notes: The LFS does not record mothers’ information from everyone but instead has a ‘relationship to head’ question which identifies the head, his/her spouse and his/her children (both married and unmarried). Only married women who identified as heads or spouses were used to construct the sample of mothers. Each figure reported in the table is an average of that category’s values across the mentioned years.

In addition, qualitative research with working women in Lahore shows many women giving up promotions or switching to less demanding careers to balance work and family responsibilities. This reflects strict societal norms around women’s reproductive roles and relatively weak provisions for working parents, compared to other countries in the region. Consequently, women in Pakistan face some of the highest reproductive burdens in South Asia, pushing them to either exit the labor market, or choose more flexible careers, often with lower remuneration.

Unspoken Burdens: What Mothers Face in the Workplace

The latest round of the Pakistan LFS shows that 63% of women in formal, fixed wage employment are employed in the Education and Teaching sector. Not only is this generally considered as a socially acceptable career for women because it is often seen as an extension of their caregiving roles, but the teaching profession is often perceived as more compatible with women’s domestic roles than a typical office job. This is because it offers greater flexibility, little overtime and extended holidays between terms. However, even teaching jobs are not free of challenges. We interviewed mothers working at a private sector university in Lahore – both staff and faculty – about the challenges they have faced at work since becoming mothers.

All of our interviewees emphasized that once a woman becomes a mother, her work experience diverges significantly from that of a man. A large portion of her time is consumed by childcare responsibilities. The mental strain of balancing work and caregiving often leads to ‘brain fog’, in which women struggle to focus and make decisions. As a result, the bandwidth available for creative or high-focus tasks decreases significantly. Moreover, the guilt of leaving one’s child behind, combined with the weight of defying familial and societal expectations that mothers should step away from work, further compounds the mental toll.

Yet, while we saw some significant overlaps between the experiences of faculty and staff, there were marked differences too. Women faculty shared that motherhood has limited their career opportunities – particularly to engage in fieldwork, which became unmanageable due to childcare responsibilities – thereby compromising their research pathways. However, they also highlighted the relative flexibility in daily teaching schedules and the option to work from home (WFH) for certain tasks that made balancing their various roles easier.

In contrast, staff members described how difficult it is to care for a sick child while adhering to a rigid 8-hour office schedule. They also lamented the lost access to hybrid work after COVID-related accommodations were rolled back. Additionally, the staff stated that there is currently no formal policy that allows for hybrid arrangements to support mothers in the workplace.

Another staff member stressed the importance of open communication around bringing children to work. Although the university has a daycare, not every child adjusts well to it, and if a mother needs to bring her child with her, she should be able to do so without guilt or fear of disapproval from her superiors. She also emphasized the need for a WFH policy, particularly in summer vacations of schools. This flexibility can help reduce the stress of juggling both work and household duties, particularly when the children are at home all the time.

Several interviewees highlighted the lack of formal support mechanisms to address these realities. They pointed out that while informal support mechanisms exist at the university, they often depend on the immediate supervisor’s attitude, creating advantages for some and disadvantages for others. The problem worsens when mothers are evaluated using the same benchmarks as men or women without children, with no adjustments for caregiving duties. This disparity underscores the need for consistent, institutional policies that acknowledge the realities of working mothers, and help them in balancing their professional and family responsibilities. One particular policy could be a concerted effort to ensure substantive female representation at senior management and leadership positions. Evidence suggests that this can shift the organizational culture to a more collaborative, people-oriented approach. Over time, such measures can significantly reduce the motherhood penalty by empowering mothers to remain productive in their careers, without sacrificing their family responsibilities . Without such changes, talented women will continue to be sidelined, a loss for families, workplaces, and society.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.