Are the walls of civic spaces closing in on women in Pakistan?

In a study conducted as part of the Action for Empowerment and Accountability multi-country research programme, we found that Covid-19 has accelerated the shrinking of civic space in Pakistan. A narrowing civic space refers to media controls, restrictions on NGOs, unions and civic associations, security threats to dissidents, backlash against rights-based activism, and curbs on the right to peaceful protests. Examining the period since the start of the pandemic, this blog focuses on some consequences of this phenomenon for women.

To accommodate the constraints placed by lockdowns on research efforts, our methodology tracked media reports and held online monthly discussions (‘observatory panels’) with key actors in civil society to discuss events and changes in real time from July to December 2020. This was supplemented with 14 key informant interviews with individuals from health, education, human rights, media, unions and low-income workers’ associations.

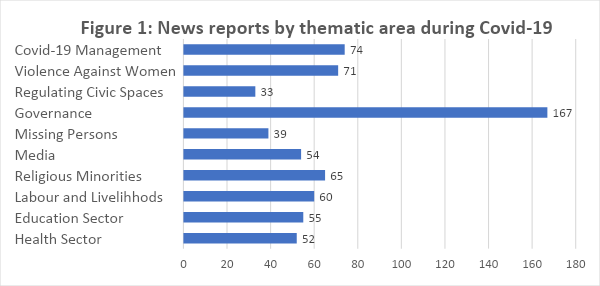

We built a repository of over 700 articles, sourced from English, Urdu and Sindhi press and social media. Coverage about civic space in terms of new debate, contention or protests was categorized thematically.

For more details on these findings, see our final report. Our research team wrote a blog, constructed a 3-D timeline and released a podcast on health workers’ protests, as well as a blog, 3-D timeline and podcast on student protests to share our rich data with a wider audience.

Impetus for violence against women and sexual harassment

The lockdown in 2020 led to increased domestic violence against women, to the growing concern of feminist activists, advocacy NGOs, some government officials, and international aid agencies alike. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa alone, over 500 cases were reported during this period. Without functioning public transport, victims were stuck at home with their abusers. Women’s shelters and support services in Sindh reported that they were unable to process cases efficiently during lockdown. The UNFPA helped the Government of the Punjab roll an app called Women Safety for use with cell phones, while the Ministry of Human Rights set up its own helpline to assist women.

Yet the motorway rape case in September 2020 only underscored the differences between progressive civil society and government perspectives on sexual violence. A senior police officer in charge of investigating the motorway rape made victim-blaming remarks and retains his position despite civil society protests. Prime Minister Imran Khan himself linked sexual violence with increased westernization of Pakistani society and suggested women should observe purdah to keep themselves safe. He repeated these views the following year in an international interview, suggesting that women’s dress code is linked to attacks because men are not “robots”.

Feminists contend that sexual violence is pervasive across Pakistani society, and is a threat to all women no matter how they dress. University students held their annual Student Solidarity March in urban centres despite Covid-19 concerns. Their demands included the establishment of committees to address a long-standing problem of sexual harassment on campuses. They also demanded the revival of student unions and internet facilities for all students. Students joined in the annual feminist Aurat Marches held in multiple cities around the country to celebrate International Women’s Day (March 8) and protest against misogyny, violence and other manifestations of gender inequality.

The media became increasingly critical of the state during the first year of the pandemic. A group of women journalists who wrote articles or posted online commentary critical of the government’s pandemic response efforts were attacked and threatened on social media by persons linked to the ruling party. Activists and media representatives signed a petition which featured the journalists’ statement. The journalists testified to the standing committee on human rights in the National Assembly on the extent of threat and harassment they experienced. Although the government denied responsibility, the effect of the harassment was a deepening of vulnerability of women active in media spaces.

Decreased advocacy for effective policy reform

The disconnect between official voices and activists on women’s issues became further apparent during the debate over policy reforms to tackle sexual violence. Prime Minister Khan promised exemplary punishment for the motorway case rapist, suggesting chemical castration and public hanging of serial rapists, while activists oppose the death penalty and argue that existing laws need to be implemented more effectively before introducing new ones. Nonetheless, a new ordinance established special courts for women and children and other measures to improve investigation for rape, and included punishments of voluntary chemical castration and hanging – but not in public.

Policymaking around violence against women remains mixed at best. A new bill to curb domestic violence tabled in Islamabad’s parliament has stalled. The Prime Minister referred it to the Council of Islamic Ideology, known for its history of drafting discriminatory laws against women and religious minorities, including the 1979 Hudood Ordinances. This year a court in Punjab declared the two-finger test of rape victims as violative of their right to dignity in response to a petition filed by women activists. But in a blow to feminists, the Supreme Court recently ruled that in sexual harassment cases the complainant must prove sexual intent.

In the past, advocacy for gender policy reform in Pakistan has made effective use of feminist NGOs, such as Aurat Foundation, Shirkat Gah, Simorgh, and ASR. These bodies have helped conduct research, raise public awareness and lobby with politicians. The 1990s campaign for the restoration and increase in women’s reserved seats in the legislative assemblies, conducted with significant support from international aid agencies, is one such story of success. Women’s NGOs have also worked in tandem with the National Commission on the Status of Women and its provincial counterparts to work with legislators to achieve policy outcomes such as changes to Pakistan’s zina laws, election reforms to protect women voters, domestic violence laws, and more.

But successive governments have only increased the registration requirements and added hurdles which impede the flow of international funds to NGOs. Citing security concerns, the government now requires civil society organizations to seek permission to hold public consultations and conduct research, along with a mandatory registration of NGOs with a new Charity Commission. This has forced a number of major advocacy NGOs to curtail their activities, reduce staff, and struggle to operate with limited funds. Our interviews suggest that donor funds will be diverted from rights-based advocacy work to less politically contentious service-delivery NGOs to adjust to these growing constraints.

Parting thought

Closing civic spaces, inconsistent gender policy-making, and political leadership that fails to grasp the complexities of sexual violence may be attempts to discourage women from speaking out in the public domain. Yet despite growing constraints on civil society organizations, and backlash from conservative groups towards feminist activism, women have continued to protest and mobilize around gender justice issues throughout the pandemic period. Our findings suggest that women will persist in crafting new openings to hold the state accountable for gender claims in the foreseeable future – a ray of hope amidst a turbulent year (one of many already) for Pakistani women.

Ayesha Khan works at the Collective for Social Science Research in Karachi, and is author of The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy (2018).

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.