Be the Solution: How Bureaucrats can Improve Public Sector Performance Through Mission Management

Management reform strategies are often steeped in a top-down, command-and-control, incentive-laden theory of change. As McDonnell puts it in the developing world public sector “current approaches advocate for abstract monitoring systems that can monitor across large scales and at a distance, assuming only a pinnacle principal can be trusted to monitor his interests”. As a result, “currently dominant approaches to state reform… seek to limit discretion”. In my work, I explore when these approaches are useful, and when they may be counterproductive.

I theorize that a managerial style that prioritizes supporting mission-driven bureaucrats to do the work they care about will in many circumstances outperform management focusing on tight monitoring and control in improving bureaucratic performance and citizen welfare. I examine managerial practices that self-determination theory suggests are likely to foster mission motivation; that is, those that:

- Allow Autonomy: give bureaucrats a zone of independent action in which to make judgments and decisions;

- Cultivate Competence: support bureaucrats in making self-directed action, fostering a sense of skill and agency, and/or;

- Promote Purpose: connect bureaucrats to results in some manner, thus creating a positive feedback loop between autonomous action and impact.

Selection and Treatment Effects

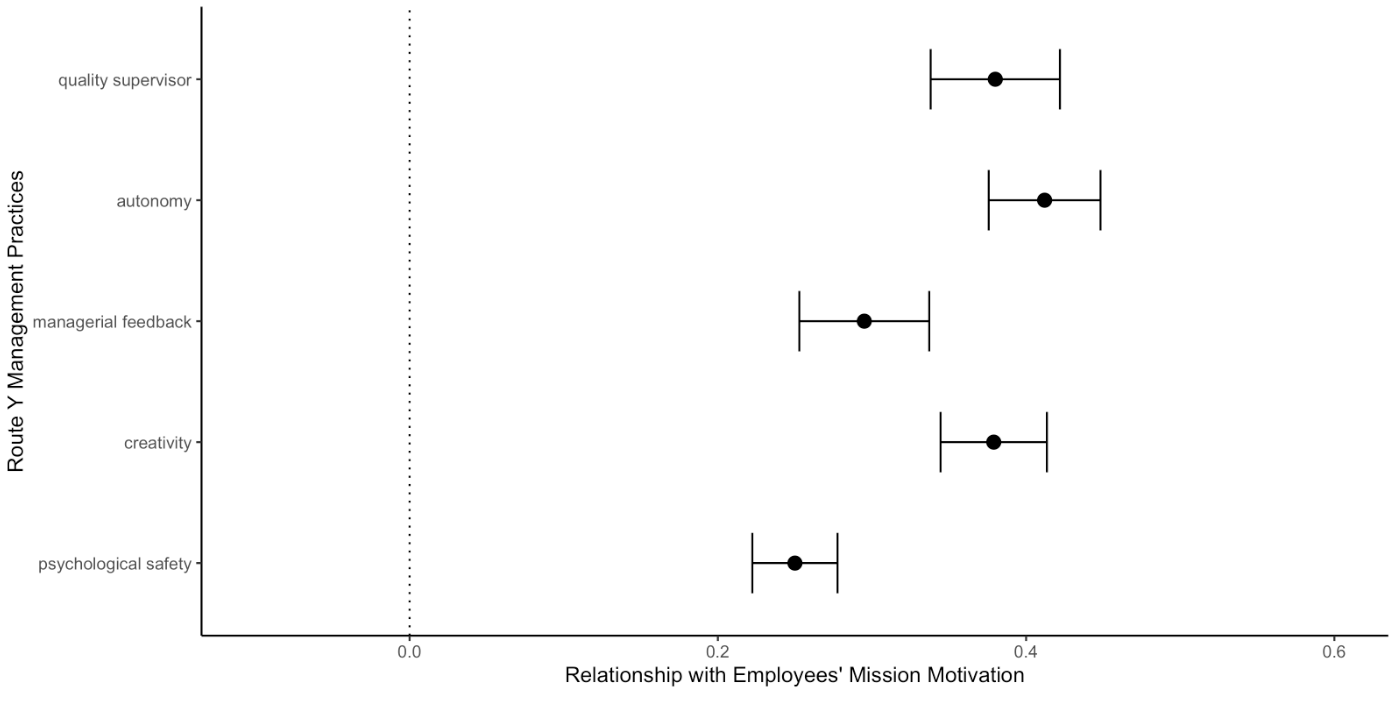

To explore this, I draw on evidence from primary empirical work in five countries and secondary econometric analysis of a database of civil servant perceptions I’ve assembled (encompassing over 4 million individual and 2,000 agency observations). I find evidence in several settings of treatment effects - with more supportive management practices inculcating intrinsic mission motivation and greater mission-driven action by existing employees. Figure 1 below draws from the database to suggest this is a general phenomenon. As perceptions of supportive management practices rise over time within an agency, so too does mission motivation.

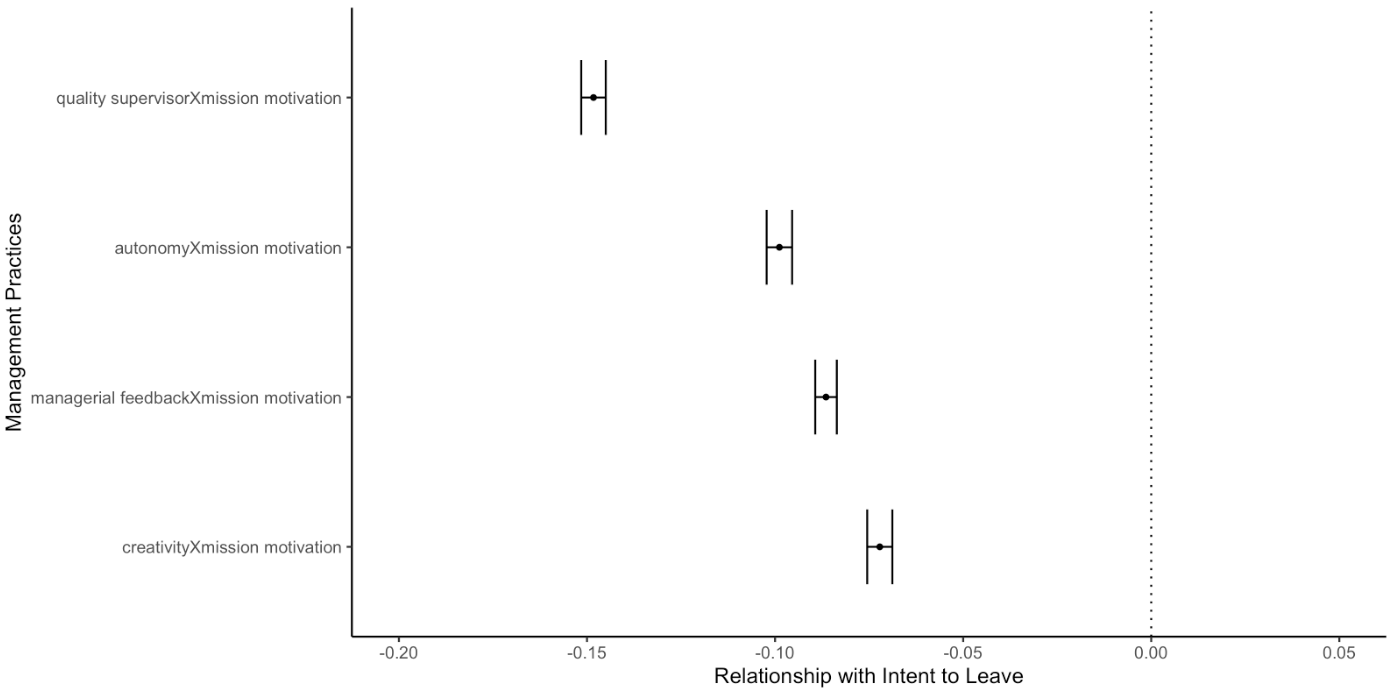

This does not mean that all individuals are, or can become, equally mission motivated. While motivation is mutable, some individuals begin with higher levels of commitment to an organization’s mission. Tightly controlling managerial practices run the risk of driving out these particularly committed employees. Figure 2 below suggests these findings also generalize; individuals with higher levels of intrinsic mission motivation are differentially likely to wish to exit their organization when faced with less supportive management practices.

Consistent with prior work, I also find that managing for mission is most successful and a tight monitoring system most counterproductive when tasks are imperfectly monitorable (which is quite frequent in the public sector). The specific management practices which best improve performance will depend on the nature of the job. Where successful, supportive management practices will leave an agency with an equilibrium of supportive management and employees who act in the spirit of an agency’s mission point, even when unobserved.

Evidence This Argument Applies to Pakistan

When I’ve presented this argument, it has been my observation that a surprising number of policymakers, scholars, and citizens react with some version of “OK, maybe that applies in X country, but that doesn’t apply here.” Of course, it’s the case that different places, agencies, and job roles may have (or be able to attract) many more or fewer mission-motivated personnel than others. But speaking in broad strokes, I see no evidence that the dynamics above apply in London but not Lahore or Lucknow (or anywhere else). Mission-driven bureaucrats are a bit like love in the movie Love, Actually; if you look for them, I’ve got a sneaky feeling that you’ll find that mission-driven bureaucrats actually are all around.

There is, in fact, a substantial amount of work consistent with the central thrust of this argument. In work with the Department of Health in Haripur (KPK) Yasir Khan finds in a randomized controlled trial that a simple intervention to encourage reflection on the organization’s mission more substantially improves child health outcomes than a pay-for-performance system. Ali & Altaf find that in Kasur (Punjab) even well-intentioned bureaucrats are often not put in a position to succeed; administrative and other burdens often overwhelm those delivering vaccines, exacerbating distrust between the state and citizens. In a randomized controlled trial recently published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, Bandiera et al. find that procurement officers in 26 districts of Punjab who are offered greater autonomy achieve greater value for money improvements than those who are offered performance pay. These pieces all speak to the potential for reforms that allow autonomy, cultivate competence, or promote purpose to improve performance – and indeed, to outperform reforms focused on tight controls even for relatively monitorable tasks like procurement.

Getting Better Results With Less Control

Tight control often seems an appropriate response to employees who are not devoted to the mission, but such an approach can also demotivate. Tight controls often minimize the damage done by the worst bureaucrat at the expense of preventing beneficial work by other bureaucrats. When mission-motivated bureaucrats are unable to make a difference for the better they may choose to leave. In their exit, public service loses precisely those individuals whose service is likely to be of most welfare benefit to citizens.

One definition of “bureaucrat” is “an official in a government department, in particular one perceived as being concerned with procedural correctness at the expense of people’s needs.” In my work, I find that bureaucrats frequently do in fact want to serve the public and the laudable missions of their agencies. Where bureaucrats are concerned with procedural correctness, I find it is often the case that this is because of management which incentivizes such behavior. When we observe a bureaucrat seemingly shirking their responsibilities, it is worth considering whether they are unmotivated or whether they are simply demotivated – their behavior is a consequence of the management environment to which they are subjected.

Managerial reforms that allow autonomy, cultivate competence, and/or promote purpose will not work in every setting, for every task, or for every bureaucrat. Nevertheless, we have good reason to believe these strategies are worth giving serious consideration – not least because they will often be easier to implement than current attempts to manage by rules and metrics that are costly, and sometimes impossible, to monitor effectively. Managing for mission deserves serious consideration for those seeking to improve public sector performance in Pakistan and far beyond.

Dan Honig is Associate Professor at University College London.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.