Crafting a Competitive Advantage for Pakistani Exporters

Exports are a critical driver of economic growth, job creation, and innovation. Despite a general agreement amongst economic experts and policymakers concerning the mounting significance of exports, Pakistan’s export share of GDP has remained below 10% for the past two decades, contrasting sharply with its regional peers (see Figure 1). In India, the share of exports soared from 8.84% of GDP in 1992 to 22.8% in 2022. For Bangladesh and China, the shares were also much higher (12.9% and 20.7%, respectively, in 2022). In the midst of inadequate macroeconomic policy management and political instability, Pakistan’s export sector faces an additional challenge linked to the growing importance of global value chains in international trade.

Source: World Development Indicators

Fueled by a combination of factors including reduction in trade barriers and information technology revolution since the early 1980s, the world economy has witnessed a drastic surge in cross-border production and supply chain arrangements over the so-called Age of Global Value Chains (GVCs). Businesses are using foreign parts and components in their production processes, and at the same time, local suppliers of raw materials are selling their output not only to their domestic buyers but also internationally to multiple countries and firms.

Take the example of manufacturing a T-shirt. Pakistan is a significant regional player in the textile and apparel industry, and many international clothing brands source materials and manufacture garments in Pakistan. While the country sources cotton and yarn domestically, chemicals, dyes, and packaging materials may be imported from other countries, depending on the complexity of the T-shirt design and sourcing strategy of the brand. This exemplifies GVCs, where businesses leverage global specializations for efficient production.

Global supply chain shifts, driven by factors such as the US-China trade tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to a “great reallocation” in supply chain activity, redirecting US imports from China towards other countries, such as, Vietnam and Mexico. In 2022, 62.85% of Vietnam’s international trade was attributed to GVCs (see Figure 2). Integration into GVCs has offered firms access to specialized inputs and technologies, allowing them to tap into more lucrative markets. According to a report by the World Bank, greater GVC participation can promote the diffusion of technology and raise productivity. Firms participating in GVCs in Ethiopia, for instance, are more than twice as productive as firms that engage in traditional forms of international trade. In Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda, demand for higher quality by global supermarket chains has improved practices in horticulture. In general, a one-percent increase in GVC participation is predicted to boost per capita income by more than one percent. In Mexico and Vietnam, the regions that experienced more intensive GVC participation, also saw a greater reduction in poverty.

Source: GVC Trade Table, World Integrated Trade Solution

Bangladesh is a great example of how GVC integration underscores its potential for driving economic growth and structural change. Since 1988, the business of exporting apparel made from imported textiles has grown on average by almost 18% a year in Bangladesh, accounting for 90% of its exports, and nearly 7% of the world’s apparel and footwear, third only to China and Vietnam (World Bank 2020).

To position itself competitively, Pakistan needs to recognize its exporting firms’ profile which is dominated by large exporters but with significant contributions from smaller players across various sectors. The largest one percent of exporters in Pakistan accounted for 46.3% of total exports in 2017 (World Bank 2022 – page 153). These large firms are embedded in global production networks, having multiple foreign affiliates, and cater to a broad set of export destinations by selling multiple products on the quality spectrum. However, administrative data shows that numerous smaller players also contribute significantly to all key industrial sectors.

Over 2010-14, most exporters in textile and apparel, footwear, and fabricated metal products, for example, were businesses with lower sales, export earnings, and import spending, compared to their larger counterparts. These smaller companies sell a wider range of products but buy fewer numbers of imported inputs. Another interesting trend observed is that by relying on less expensive inputs, smaller exporters achieve lower prices compared to larger exporters. Despite obvious challenges, the configuration of exporters in Pakistan presents itself as an opportunity for integrating into GVCs. By strategically diversifying products and focusing on higher-value niches, smaller exporters can play a key role in GVC integration.

Pakistan’s Strategic Trade Policy Framework (STPF) 2020-25, as specified in the annual report of Trade Development Authority of Pakistan, aims to transform the regulatory environment to facilitate integration into regional and global value chains. This integration will require a multilayered management to reformulate industrial and trade policies for exporters, particularly, small and medium enterprises.

First, it is critical to address Pakistan’s complex regulatory regime to improve export competitiveness and sustain productivity upgrades. Due to size-dependent industrial policies, firms in Pakistan are often discouraged to grow. Instead of unconditional transfers and incentives offered to exporters, there needs to be a greater focus on providing access to finance and technology that allows young businesses to catch up with incumbent firms (Wadho, Goedhuys, and Chaudhry 2019). Improving worker productivity is another key ingredient in gaining competitive advantage (World Bank Group 2022) It entails reforms at both sectoral and macroeconomic levels to address frictions in product, labor, and financial markets, as highlighted in this conversation.

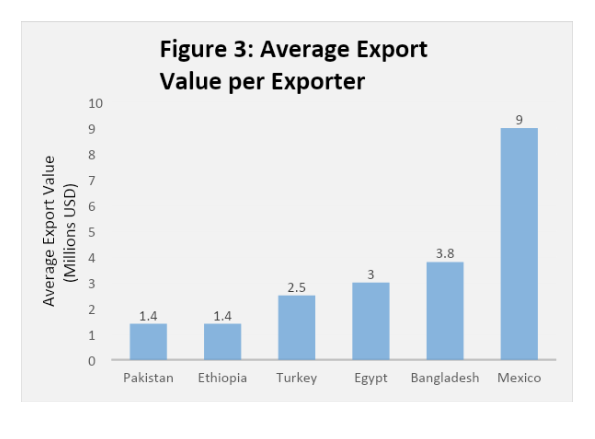

Second, it is important to diversify Pakistan’s export portfolio to include higher quality products that contribute to greater value-addition in the vertical chain of production. An average Pakistani exporter ships $1.4 million worth of merchandise a year, compared to, for example, $3.8 million by an average exporter in Bangladesh, as indicated in Figure 3. For small businesses to climb up the quality ladder, it is vital to invest in meeting international quality standards and conducting market research to build globally recognized brands, as has been the case for the Brazilian cosmetics company, Natura, and construction materials supplier, Cemex, in Mexico. The textile sector continues to receive the largest share of duty concessions, subsidised energy, and access to cheap credit – information technology, pharmaceutical and engineering sectors, amongst others, are potential sectors to target for value addition.

Source: Exporters Dynamics Database; World Bank 2022

Third, facilitating a smoother cross-border movement of goods is imperative. In most GVC integrated countries, episodes of export growth have been shown to be linked with episodes of import growth. In Pakistan, tariffs on intermediate goods are high, averaging 8%, four times the average in East Asia (World Bank 2020). An attempt to lower import bills by imposing high tariffs on imported raw materials creates market distortions and ultimately lowers export competitiveness. There are other, obvious benefits of maintaining long-term relationships with foreign partners, such as, reducing information frictions and downward renegotiation of prices charged. Imposing trade restrictions lowers efficiency by hurting prospects of global networks formation.

Finally, incorporating sustainable practices into production processes can be used to attract global customers and businesses. According to a recently announced deal between the European Parliament and Council of the European Union, all businesses based in EU countries are required to report on imported products that are carbon emission-intensive. In other words, Pakistani businesses may lose competitiveness in the international market unless they invest in sustainable energy. Knowledge flows between globally connected firms can facilitate the diffusion of environmentally friendly production techniques.

Pakistan’s export competitiveness is a critical aspect of its economic growth, and creation of niche products is a promising strategy to diversify the country’s export portfolio. Strategic policies, such as the Textiles and Apparel Policy 2020-25, as well as National Tariff Policy 2019-24, seek to improve Pakistan’s export competitiveness by encouraging value-addition along the vertical chain of production. In addition, the National Priority Sectors Export Strategy initiative is geared towards strengthening competitiveness of both emerging and established sectors through close collaboration with industry leaders. GVC integration is a multifaceted endeavor that will require coordinated efforts to support small and medium firms, streamlining regulatory processes, and greater collaboration between the government, private sector, and academia.

Zara Liaqat is an Assistant Professor at Wilfred Laurier University, Canada.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.