Girls’ Education: filling the gaps?

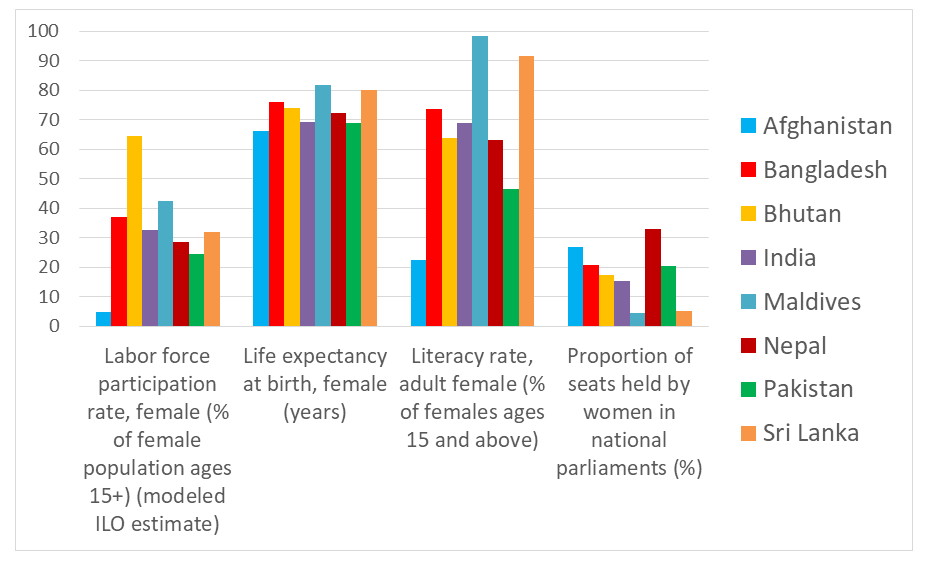

Pakistan remains amongst the world’s bottom-ranked countries year after year in the Global Gender Gap Index. A plot of the sub-components of the Index for South Asian countries in Figure 1 shows Pakistan performing worse on three of the four indicators (labor force participation rates, literacy rates, and life expectancy) than all other countries in the region, with the exception of Afghanistan.

Figure 1: Global Gender Gap Index Sub-components for South Asia

Source: World Development Indicators 2024

Our poor performance in health and education outcomes is also reflected in our downward slide in the Human Development Index. With a score of 0.54 and a rank of 164 out of 193 in 2023/24, we witnessed a decline of seven slots placing us below our regional neighbors and at par with Sub-Saharan countries. While methodological changes (HDI now ranks 193 countries as opposed to 189 previously) and the continued post-COVID macro-economic crises are partly to blame for our performance, it is also undeniable that we are in the midst of a human capital crisis.

With an estimated 22.8 million children out of school, 64 percent of our population under 30 years of age and youth comprising 61 percent of the unemployed, is it any surprise we are seeing declining productivity levels in this country? Clearly, the promise of the demographic dividend is far from being achieved. Pakistan has also been witnessing rising inequalities and little to no upward intergenerational socioeconomic and occupational mobility: all factors intrinsically linked to the quality and scope of educational outcomes. In this, girls’ educational outcomes are especially poor. In this piece, I focus on the state of gender gaps in education in Pakistan, highlighting the demand and supply side reasons behind our poor performance while laying out the space for interventions. In the end, I make the case for why it is essential for us to seriously and consistently work on reducing these gender gaps if we are to make real headway in sustainable economic growth while also delivering on our constitutional promise of education as a fundamental human right.

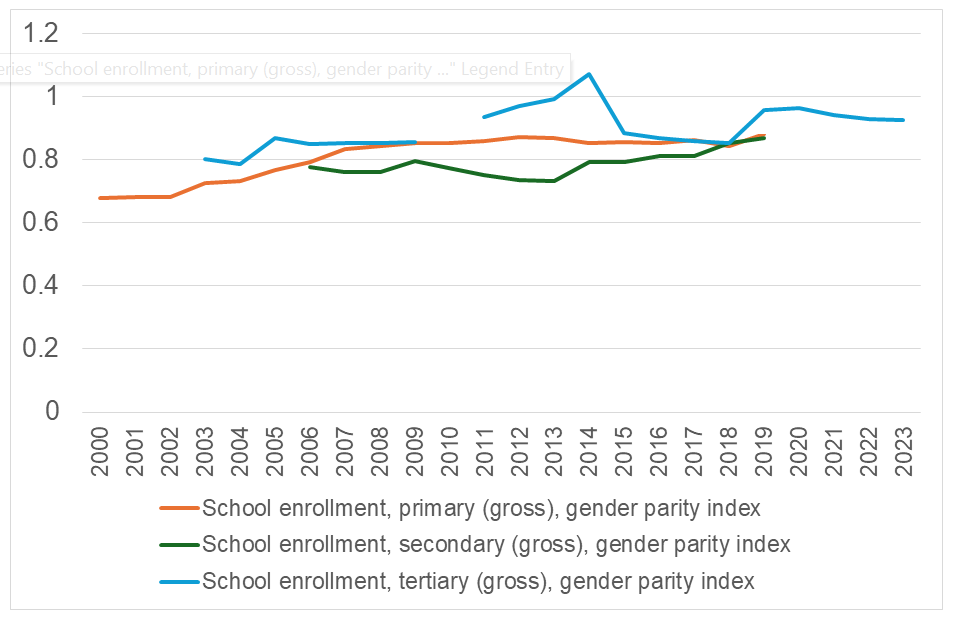

Plots of Pakistan’s gender parity index in primary, secondary and tertiary gross enrollment rates since 2000 shows that girls are at a disadvantage relative to boys particularly when it comes to secondary school enrollments (Figure 2). This is unsurprising given that the demand and supply constraints underpinning the gender gap in enrollment are heightened as girls become eligible to enter secondary school.

Figure 2: Gender Parity in Gross Enrollment

Source: World Development Indicators, 2024

Work on Pakistan shows that school infrastructure matters when parents look to enroll their children, particularly their daughters. In this, the presence of a boundary wall and that of (gender segregated) toilets becomes key as girls get older. Similarly, as girls hit puberty, typically around the age where they become eligible for secondary school enrollment, norms around purdah mean that the gender of the teacher becomes of critical importance. Hence, schools that lack women teachers see higher dropout rates for girls.

Distance to school is another key variable driving gender gaps in enrollment. The greater the distance to school, and so the larger the transport costs, the lower the likelihood that parents will enroll their children, especially girls in school. The induced dropout rates from the associated safety concerns becomes particularly acute at the secondary school level not just because parents have higher safety concerns for older daughters, but also because the supply of secondary schools is significantly lower than that of primary schools. Here, it is worth noting that high primary to secondary school ratio that we see in Pakistan is not unique. Schools are increasingly costly to set up as we move up the educational ladder thereby reducing their supply: Pakistan has approximately 182,600 functional primary schools as opposed to 34,800 secondary schools. This in turn has direct effects on transport costs to school.

Increases in direct costs of schooling (due to rising transport costs) combine with indirect cost effects to further depress demand for girls’ education beyond primary schooling. High domestic burdens alongside under-developed labor market options for women with secondary schooling mean low net returns on investment in girls’ education. For financially constrained parents, this often means that they “pick winners” and invest in that child’s education where net returns are higher: namely, boys. Yet, much of this calculus is reversed when it comes to tertiary schooling.

Indeed, 2011-2014 witnessed a climbing trend in the gender parity index at the tertiary level. Peaking at 1.07, the index revealed higher enrollment for girls relative to boys in tertiary schooling showing that amongst children who survive through secondary and move onto tertiary, the ratio becomes skewed in favor of girls. This is unsurprising given that at this level, boys are under increasing pressure to join the labor force. Besides, girls’ tertiary school enrollment serves a dual purpose of delaying their age of marriage while also potentially increasing their “value” in the marriage market in much the same way as that observed in India.

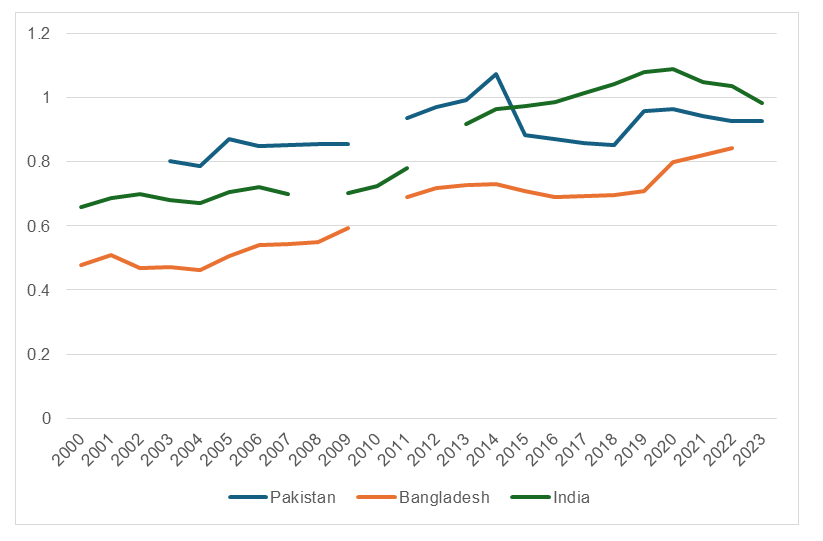

Figure 3: Gender Parity Comparisons – Tertiary

Source: World Development Indicators, 2024

However, since 2014, there has been a decline in gender parity at the tertiary level, dipping to come to par with the gender parity index in primary schooling in 2019 (Figure 2). And while the index picked up again, its levels have stagnated while hovering below 1 albeit at higher levels than both the primary and secondary indexes (figure 2). Of greater concerns is that while we were outperforming both India and Bangladesh up till 2014, both countries have caught up, with India surpassing us and Bangladesh’s trend outstripping ours (Figure 3).

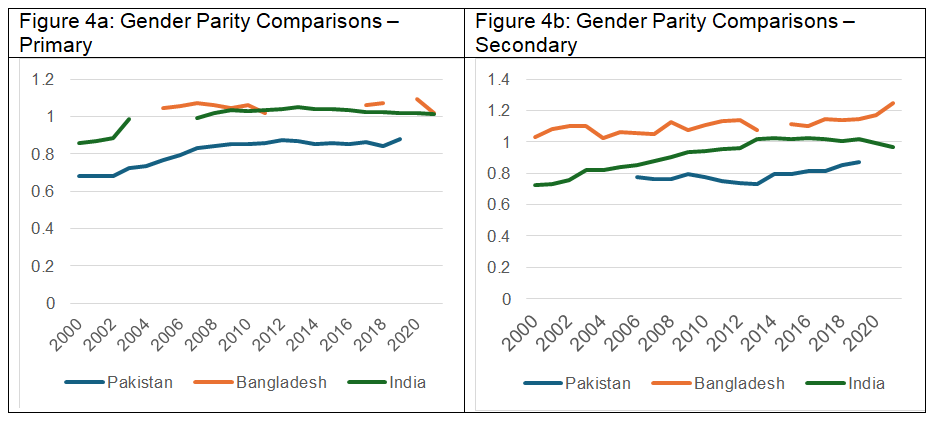

In fact, cross-country comparisons of gender parity in primary and secondary school enrollments of Pakistan with India and Bangladesh reveal that while the latter two achieved gender parity in primary enrollments in 2008, we have managed an increase from 0.84 to only 0.88 since then (Figure 4a). Similar trends hold for gender parity in secondary enrollments across the three countries (Figure 4b).

Source: World Development Indicators, 2024

Why are these persistent gaps in education of concern? Of course, education is a fundamental human right enshrined in the Pakistan constitution and its intrinsic value is indisputable. Girls’ education, however, also has tremendous instrumental value. Not only would reducing gender gaps in education increase labor productivity, thus raising GDP, but also shape their bargaining power, such as in household decision-making, fertility decisions, and the ability to adequately care and provide for (future) children. Girls’ education then has immense multiplier effects and has been empirically shown to have some of the highest rates of returns on investment.

Recognizing these benefits and in line with Article 25-A, there have been numerous interventions in the past few decades aimed at improving enrolment and reducing dropout rates. The recently launched free bus transport for girls initiative in Islamabad is one such example. BISP’s Taleemi Wazaif that ties cash transfers to school attendance with transfers to girls outstripping that for boys and increasing in value at higher grade levels is another. Similar conditional cash transfers in Latin America have been highly successful in reducing gender gaps in educational outcomes. Post-COVID there has also been an increased use of tech in underserved communities to connect students to teachers. Such interventions could be exceptionally useful where mobility constraints or those surrounding infrastructure availability remain high. However, the lack of access to mobile phones, the close monitoring of device use by girls, and issues of internet and electricity outage pose significant challenges when it comes to ed-tech interventions.

The fact of the matter is that the scale and scope of the interventions remains too small. In Pakistan, they are also often left unevaluated effectively enough to inform improved implementation design. To affect the type of sustained change that we need in the education sector, we need the range, depth and quality of interventions to be significantly improved. We also need better and closer coordination between the many actors that are currently operating in the education landscape. In all this, the role of the government remains central.

Hadia Majid is Chair of the CNM Department of Economics at LUMS

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.