High-stakes Accountability for Public Sector Education Management: a Process Trace from the Punjab

For most countries, certainly Pakistan, the state remains the largest and most significant provider of services. Implementation of service delivery and reform happens via bureaucracies at the provincial, district and sub-district levels. Very little empirical knowledge exists to explain operational or governance aspects to bureaucratic practice, especially in Pakistani service delivery reform efforts such as education.

The global evidence base on implementation practices and reforms, while thin, offers some insights. Implementation is often framed around the notion that weak governance is rooted in weak accountability. Solutions to implementation challenges in developing countries typically employ designs and techniques aimed at disciplining middle-tier bureaucrats and frontline workers, ensuring rules are followed, and by restricting discretionary space. Recent work on public management argues that high-stakes accountability measures focused on control and monitoring are counterproductive to managerial performance, whereas more autonomy for decision making and executive practice correlates with higher productivity of bureaucrats. Our findings from a study of an education service delivery reform in Punjab contribute to the evidence on bureaucratic practice, and the ways in which it is or isn’t altered in response to accountability reforms.

In 2011, Punjab introduced a high-stakes, data-driven accountability approach that sought to improve delivery and outcomes of education by changing managerial practices of middle- and lower-tier bureaucrats. Using a retrospective qualitative design, we trace the enactment of the approach used between 2011 and 2018 to describe how managerial practices of middle- and lower-tier bureaucrats changed. We probe bureaucrats’ experiences, perceptions and beliefs regarding new routines, and the ways in which routines and practices cascaded from the provincial to the district and sub-district levels.

The approach

The reform introduced in Punjab – called the Punjab Education Roadmap - was a form of a centralized accountability-driven approach. At the core was a political oversight model which leveraged political capital of the apex provincial office -that of the Chief Minister - to orient bureaucratic structures involved in service delivery towards improvements at a fast pace. Second, the approach deployed an extensive ‘data regime’ – the use of infrastructural and access data disaggregated at the district level to make visible locations and schools that were lagging. Both components informed a setting of particular routines and their commensurate practices. Stakeholders in the provincial capital set targets for the 36 districts that were reviewed regularly every quarter during high-level monitoring (‘Stocktake’) meetings, where district executives reported progress. District executives of well-performing districts were rewarded; those of poorly-performing districts were sanctioned.

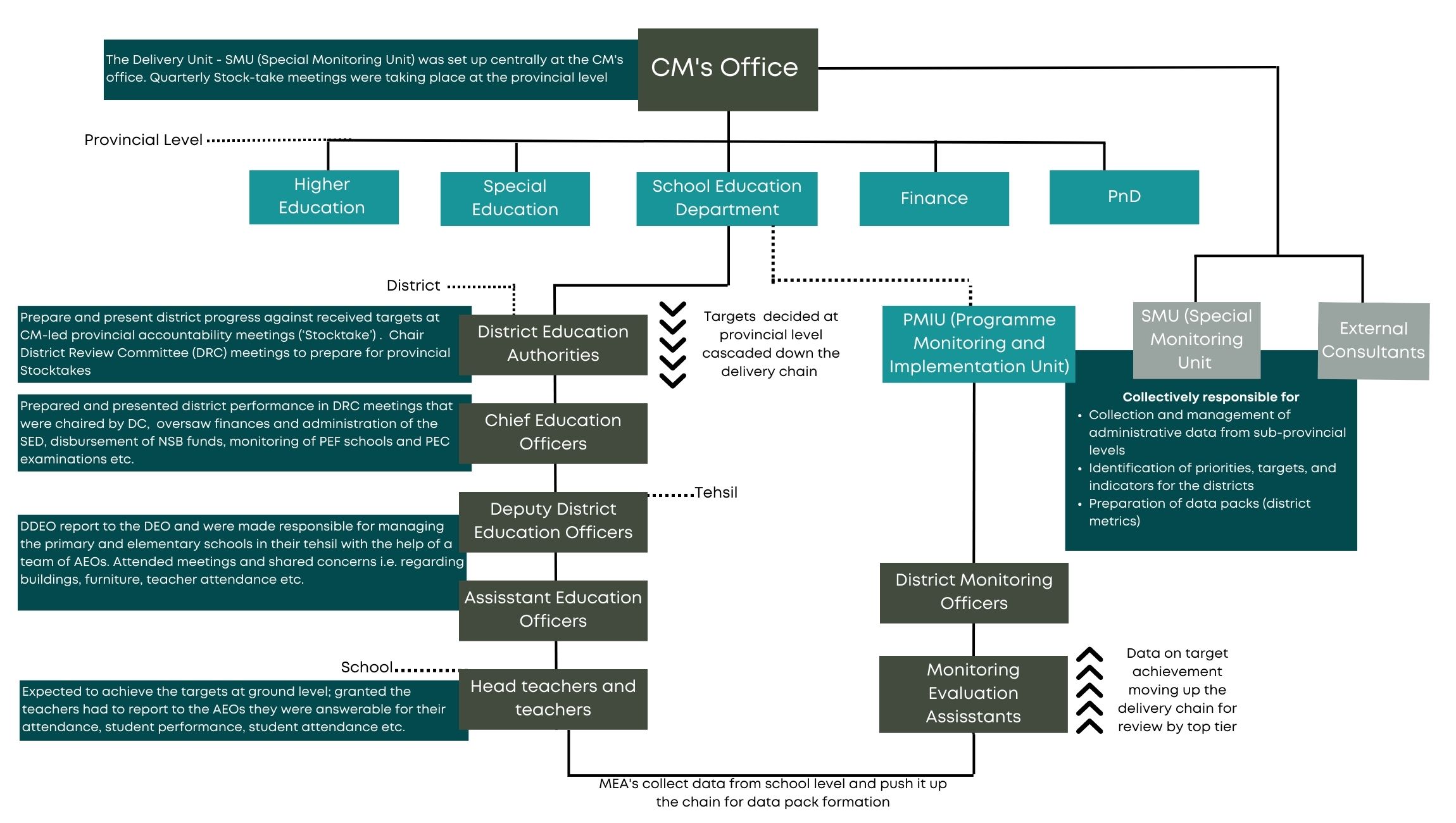

The diagram below captures the structure and commensurate responsibilities allocated by the Punjab Education Roadmap. It also demonstrates the centralized authoritative structure of the approach: the targets were set centrally and communicated down the delivery chain, while data on monitoring that was collected at the school level was sent up the governance hierarchy where it was used in high-level meetings to hold district bureaucracy accountable.

Incentives, accountability and political sponsorship

Accountability was at the heart of the delivery reform approach in the Punjab. All other practices (of political sponsorship, target setting and monitoring) were feeding into this accountability process, as part of which quarterly meetings called Stocktake meetings were convened by the Chief Minister. Thirty-nine Stocktake meetings were held over 7 years (every 3 months) – many of these meetings lasting up to 4 hours. These meetings involved presentation of data on key indicators gathered via an extensive education management information system, and processed in the form of heat maps disaggregated at the district level. On-track districts were marked as green and off-track districts were flagged in red.

In the absence of any formal changes to performance evaluation rules of the District Coordination Officers (DCOs)/Deputy Commissioners (DCs)[1], the high-stakes accountability mechanism in this delivery approach worked through two channels: i) the Chief Minister chairing the Stocktake meetings, reviewing targets for each district and asking questions about lack of progress and ii) competition between peers. Compliance with Roadmap targets therefore became significantly dependent on perceived implications of the Chief Minister’s reactions to district performance, as well as on peer effects.

The presence of the Chief Minister as Chair sent a strong signal of political ownership of this reform – an emphasis to the bureaucracy that it had to be taken seriously. The Stocktake experiences confirm that this understanding existed among district executives:

It used to be a very interesting and difficult time, when those meetings were scheduled after every two months. There was a reform unit in the CM’s office. They used to make presentations to the CM, where they would show with green and red colours what was on track and what was not. There was a lot of preparation for these meetings. The meetings were taken very seriously because there used to be a lot of accountability in the meetings by the CM at the highest level for all areas where the targets weren’t met or the progress was slow. So that was very effective. Because everyone was on their toes.(DC Dera Ghazi Khan)

The constant monitoring by the Chief Minister and the Chief Secretary played a very critical role. The Stocktake used to happen after every 3 months. The system itself was also set up in a way [that it created an incentive]…so it was a very big factor that the CM himself after 3 months would chair the meeting, and the top 3 district executives would get congratulated and the 3 bottom ones would get reprimanded. (DC Mianwali)

I mean, if I talk about myself, we were two to four friends so we would, at night, share our notes going like, ‘Which position is your district?’ Some would say ‘I’m in the red,’ then say a few curse words that ‘the EDO got me killed this time.’ So in this, to some extent, DCOs would coordinate between each other. So that was fear plus passion; it became a routine of ours to run the roadmap for education as well as (other sector). (DCO Nankana Sahib)

While the new routines and practices resulted in considerable activity, compliance and a competitive spirit amongst the DCOs/DCs at the district levels, this authoritative centralization cascaded down the delivery chain in ways that engendered a culture of fear at the lower tiers of the delivery chain (among Deputy District Education Officers (DDEOs), Assistant Education Officers (AEOs) and schools) regarding outcomes that would lag despite district-level efforts even by education bureaucrats themselves:

The Stocktake meetings and DRC (District Review Committee) meetings were probably the least effective part of the reform in my view. As I said before, there was a real sense of fear and foreboding due to these meetings. There was a tension that also impacted our health and our personal lives. And sometimes we were given targets that were not achievable nor realistic. So these things I found a bit negative. The rest of it is that school performance improved because of these practices. (DDEO Kasur)

The sustainability challenge

Another key finding from the study is that most of the routines and practices introduced ceased once the political ownership receded. Our interviews suggest the biggest obstacle to the Roadmap’s persistence despite change in political leadership may have been an overall lack of bureaucratic ownership of the delivery approach, especially at sub-district levels. In response to high-stakes accountability, bureaucrats focused far more on compliance of process rather than understanding its intended outcomes through a change of bureaucratic practice or attitude. As a former DCO from Chakwal explained:

Look, in our society, a lot of things that drive you are to do with convention and respect and we have drawn the parameters of respect ourselves. We do not want to be punished in front of our colleagues. We don't take criticism as criticism; we take it as punishment or a bad word. So because that happened, people would work really hard.

Additionally, the cascade of the incentives and accountability down the delivery chain happened in complex and, arguably, incomplete ways. While some practices cascaded (the meetings for monitoring and high-stakes accountability), other practices did not (such as bonuses for good performance). The DRC and pre-DRC meetings, which mirrored the Stocktake meetings, were attended by district education department staff and were held monthly. But as our data suggests, much additional activity was undertaken to prepare for the pre-DRC meetings as well, often to the frustration of grassroots bureaucrats in education:

The least effective were the limitless meetings because of which we would get impacted and we would move away from the main point of focus and we would start focusing on unimportant things. (Executive District Officer (EDO) Lahore)

The least effective was that a person who had just passed Matric (Grade 10), we would be running around the place because of his reporting; we would get flagged red. (DDEO Kasur) Everything [in terms of effectiveness] was 50/50. Because when these meetings used to happen we used to forget the real purpose, and we would get busy trying to fulfill these tasks [that we were asked to do]. The real purpose is to teach the children and that would get neglected. The tension of the meetings and monitoring was the least effective (aspect of the reform) because the entire work week would go into preparing for these meetings. (DDEO Rawalpindi)

An anecdote recounted by a District Education Officer during their interview highlights a unique case: a member of the civil bureaucracy (the DC Attock) made an effort to reward the education bureaucracy (District Education Officer and team) for their support in preparing for the quarterly Stocktake in Lahore by treating them all to a dinner near Tarbela Dam in Swabi, KP. By moving the reward structure away from just himself to those who had helped him win high-level political appreciation from the Chief Minister, the DEO recalling the story observed, ‘This increased everyone’s motivation level.’

Key takeaways

A lot of useful service delivery actions and process/target compliance can be generated in response to the introduction of accountability mechanisms in a public system, even ones that are not formally linked to performance evaluations. In Punjab, during 2012/18 this was done through a top-down accountability approach that were pushed through by leveraging abundant political capital (where available), and the approach did make the system respond.

Yet the responses do not necessarily mean practices have been internalized or are fostering higher levels of motivation. Changes to practices and routines are unlikely to persist structurally unless there is ownership and understanding of the reform motive at the middle and grassroots levels. This is especially true at lower tiers of delivery, which are several layers removed from the centre of motivation (high-level political actor), and where a culture of fear is most likely to take root.

The big lesson here, then, is that a successful and impactful delivery approach design should consider the ways in which mid-tier and frontline bureaucrats are likely to receive, interact and adapt to the reform in question. Where the burden of high-stakes accountability is distributed vertically across systems, so too should commensurate rewards and compensations. Doing so can improve the necessary alignment between authority, responsibility and accountability that lies at the heart of accelerated service delivery efforts.

[1] Arguably, the structure of the bureaucracy and the core set of incentives that the bureaucrats are trained and conditioned to respond to remained unchanged prior to, during and after the delivery approach in Punjab.

Rabea Malik is the CEO and Fellow at IDEAS.

Faisal Bari is Dean SOE and Fellow at IDEAS.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.