Pakistan’s Battle for Clean Air: Will Our Cities Ever Be Breathable Again?

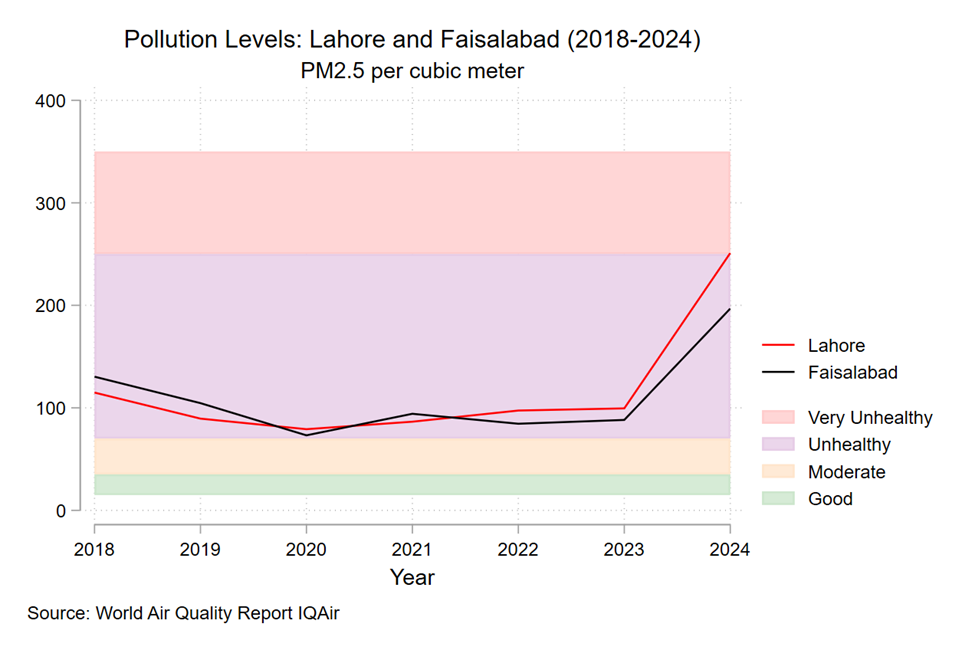

Since 2016, smog has become the notorious ‘fifth season’ of Pakistan, characterized by high concentrations of air pollutants, low visibility and severe socio-economic disruptions. Every October, the season begins with a faint burning smell in the air, quickly escalating into a thick yellow haze that blankets the sky. Figure 1 shows a rapid increase in PM2.5 levels in Lahore and Faisalabad from 2023 to 2024.

Figure 1: PM2.5 Levels in Lahore and Faisalabad (2018-24)

The sudden rise in air pollution from 2023-24 in these cities could be attributed to the following factors: vehicle emissions, industrial pollution, crop residue burning, and the widespread use of fossil fuels. According to the environment protection authorities of Pakistan, around 30% of this pollution is coming from crop burning in India. In addition, Hiren Jethva (a senior research scientist at NASA) has claimed that a significantly higher number of crops have been burnt in 2023-24 than the previous years.

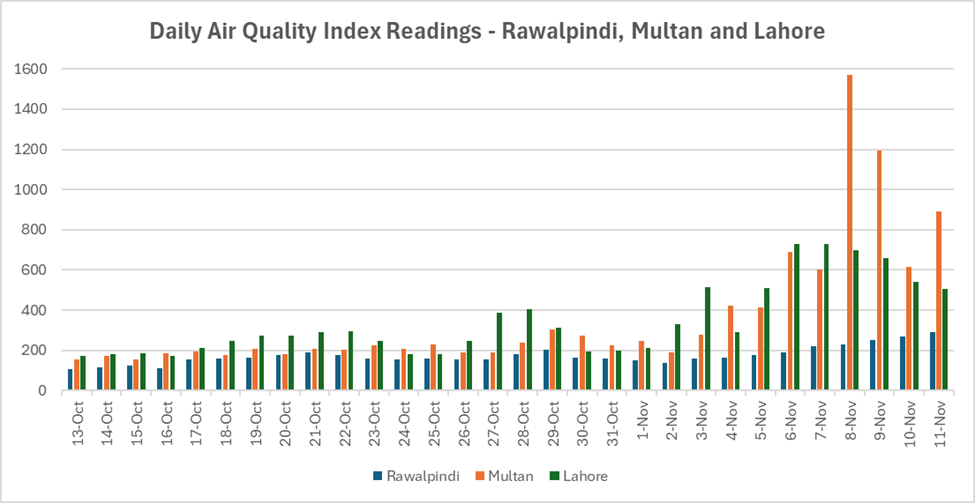

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Air Quality Index (AQI), a reading below 50 indicates good air quality, while anything above 300 is classified as hazardous. Pakistan’s densely populated urban centers are bearing the brunt of the smog crisis. On 8 November 2024, Multan topped the list with a staggering AQI of 1,392, followed by Lahore at 826, Peshawar at 575, Haripur and Rawalpindi at 271 and Islamabad at 245.

In response to worsening smog crisis, the government has implemented emergency measures, including closing primary schools for a week, mandating the early closure of commercial areas, promoting work-from-home under a "green lockdown," and restricting motorized rickshaws. However, it’s high time we move beyond these temporary fixes and focus on permanent solutions. In this blog post, we explore the primary causes and impacts of smog in Pakistan’s urban centers, critique the government's current short-term policies as mere band-aid solutions, and suggest long-term strategies inspired by successful approaches from other countries to effectively tackle this pressing issue.

Understanding the Smog Crisis: Causes and Effects

Smog is mainly composed of ground-level ozone and particulate matter i.e. PM2.5. The leading causes of smog in Pakistan’s major cities include crop residue burning, rapid industrialization and urbanization, the surge in vehicles using low-quality fuel, emissions from brick kilns, and widespread deforestation.

Figure 2: Factors contributing towards air pollution in Punjab 1990-2020 (Source: CM Punjab Smog Mitigation Plan)

According to Figure 2 above, transportation is the biggest polluter in Punjab, contributing a staggering 83.15% of the total pollution, followed by industries at 9.07%, energy production at 3.9%, waste burning at 3.6%, and commercial and domestic activities making up the remainder. Lahore consistently ranks among the top 10% most polluted cities in the world and has seen a sharp increase in registered vehicles, especially two-stroke motorbikes, scooters, and auto-rickshaws, which further exacerbates the air quality crisis. However, the availability of LNG has somewhat reduced reliance on biomass burning, keeping emissions from the domestic sector relatively low. Nonetheless, burning of crop residue (3.9%) and waste (3.6%) on the outskirts of Lahore adds to the problem. In November 2024, Lahore and its 13 million residents were engulfed in thick smog, with the AQI frequently crossing the 1000-mark in various parts of the city—well above the hazardous threshold of 300. Environmental authorities in Pakistan estimate that around 30% of Lahore’s smog originates from across the border in India.

Additionally, on November 8, 2024, Multan’s AQI surpassed the 2000-mark, making it one of the most polluted cities in the country. The smog crisis has extended to nearby districts like Bahawalpur, Muzaffargarh, and Khanewal, where air quality has similarly deteriorated, leading to severely reduced visibility on the roads.

Figure 3 represents the daily AQI readings for Rawalpindi, Multan and Lahore, from 13 October to 11 November 2024. The graph underscores the severe smog problem in all three cities, with a critical peak in early November.

Figure 3: Daily AQI Readings for Rawalpindi, Multan & Lahore, 13 October – 11 November 2024. Source: IQAir

Inhaling smog-filled air poses serious health risks because it contains ozone, a harmful pollutant. High levels of ozone can irritate the respiratory system, reduce lung function, and worsen asthma symptoms. It can also inflame and damage the lung lining and exacerbate chronic lung conditions like emphysema and bronchitis. An AQI exceeding 500 is akin to smoking 30 cigarettes a day, significantly cutting life expectancy by nearly 7 years in highly polluted areas such as Lahore, Sheikhupura, Kasur, and Peshawar. In 2021, particulate air pollution was estimated to reduce the life expectancy of an average Pakistani by 2.7 years. At the start of November, approximately 900 people were hospitalized in Lahore due to severe respiratory issues.

According to the WHO Global Health Observatory, around 200 deaths per 100,000 people in Pakistan are attributed to environmental factors. The World Bank estimates that outdoor air pollution in Pakistan results in about 22,000 premature deaths and leads to a loss of 163,432 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) annually.

The Government’s Role: Tackling Smog or Just Managing the Crisis?

The Government of Punjab has chalked up a comprehensive Smog Mitigation Plan, which targets all major sectors like transport, industry, and agriculture. Any efforts to prevent smog must include an effective plan to mitigate transport pollution emissions. The Plan outlines the introduction of 5,000 electric buses, an e-bike scheme for college / university students, penalties for pollution laws violations like route permit cancellations of non-certified smoke emitting vehicles, among other steps. However, it lacks the development of a significant incentive scheme to shift people’s behaviors from using private transport and towards public transportation. As long as people (especially the sizable middle class) find private transport cheaper, more reliable, convenient, and safer than public transport, they will not prefer public transport over private transport. Thus, policies which incentivize the use of public transport coupled with existing policies in the Plan to penalize non-compliers of vehicle emissions must be a part of a long-term smog prevention action plan.

While the Smog Mitigation Plan is a step in the right direction, the government needs to concentrate more efforts towards long-term smog prevention as opposed to economically expensive and remedial activities like artificial rain which was retroactively implemented last year and again this year when smog levels were very high. Similarly, school and office closures are retroactive measures that the government imposes each year at serious economic costs to society.

Also, as evident by worse AQI levels compared with last year, the government’s efforts to discourage crop burning were not sufficient. While efforts were made to distribute super seeders (specialized agricultural machines which directly sow seeds into a field) to farmers, these efforts fell short of the required scale.

A Long-term Vision: What Should Be Done Instead?

We can draw lessons from our neighboring country China, which was also suffering from high air pollution for several years. The Chinese government launched the Air Pollution Action Plan in 2013, which helped in reducing PM2.5 levels by 33% in Beijing, from 2013 to 2017. The government attempted to cut the consumption of coal by shutting down coal mines, banning new coal-fired power plants and shutting down several old ones in the most polluted regions of China. Moreover, the government restricted the number of cars on the road and introduced electric and LNG bus fleets and taxis. Furthermore, the government introduced afforestation and reforestation programmes such as the Great Green Wall project, which helped in planting 35 billion trees across 12 provinces. Additionally, the government set up the Green Financial System, which incentivized private investment in green sectors, and disincentivized investment in the polluting sectors.

Although Pakistan already has a tree plantation program, that alone will not be sufficient to combat the problem of smog. Unlike China’s centralized government structure, Pakistan has a decentralized government structure, which requires effective coordination between federal and provincial governments to implement policies. China also had adequate financial resources to support the measures mentioned above, which is not the case for Pakistan.

Dr. Sanval Nasim (Assistant Professor of Economics, Colby College) emphasized the pressing need for reallocation of resources to increase the government funding provided to the Environment Protection Department (EPD). Currently, the EPD lacks adequate staff and technical expertise to deal with complex environmental issues like smog. Increased funding can be utilized in hiring skilled professionals and introducing performance-based incentives for EPD employees. It can also support collaborations with universities, think tanks and international organizations to come up with innovative and long-term solutions to this problem. Additionally, Dr Nasim remarked that more source apportionment studies should be conducted in the most affected areas of Punjab, in order to identify the sources of air pollution. The findings of these studies will help in developing plans to improve air quality and reduce the intensity of smog.

According to Miss Nazish Afraz (Visiting Faculty at LUMS and Economic Consultant), the Government needs to implement a long-term urban plan for all the major cities in Pakistan, which are suffering from hazardous levels of air pollution. The high reliance on cars, two-wheelers and rickshaws needs to be reduced. This can only happen if the cities become pedestrian-friendly and walkable and public transport becomes accessible and safe for all residents, especially women, who feel unsafe in buses and on roads. In addition, the locals should play their part in reducing congestion on roads by engaging in carpooling.

The road to breathable cities may be long but with strategic effort and investment, Pakistan can secure a safer and healthier future for its citizens.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.