Pakistan's Children are not Learning: What Can We Do About It?

In a primary school in the heart of Rahim Yar Khan, Punjab, 8-year-old Abida struggles to recognise words while reading a paragraph from her Grade 2 Urdu textbook. For her, reading is a slow laborious process, as she painstakingly sounds out words, often stumbling over pronunciation. Meanwhile, her classmates make significant progress, further deepening her sense of frustration. Over 500 miles away in Charsadda, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 6-year-old Khushal faces his own challenges during a mathematics lesson as he tries to count in sequence up to 20. He starts off confidently, counting “1, 2, 3…” but hesitates at 5, suddenly jumping to 8 and leaving out 6 and 7 entirely. This pattern is repeated, drawing giggles from classmates and visible impatience from his teacher. Khushal's cheeks flush with embarrassment.

These two scenarios are all too common in schools across Pakistan – a country grappling with an acute learning crisis. To address this challenge, the Pakistan Foundational Learning Hub, a unit of the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training, has been set up to improve basic literacy and numeracy outcomes across Pakistan, and our recent Pakistan Foundational Learning Landscape Analysis has explored this issue in depth.

Approximately 26 million children remain out-of-school in Pakistan. For those actually attending school, the quality of learning often falls short; many struggle to read grade-level texts even in their own language or to develop basic numeracy skills expected for their age. In 2022, 77% of children in Pakistan were in ‘learning poverty’ - to read and comprehend a simple, age-appropriate text by age 10. The most vulnerable groups are disproportionately impacted in such crises; for example, learning poverty is highest among the poorest communities, and children from impoverished backgrounds are more likely to be out of school, especially in rural areas. Recent evidence shows that 82% of Grade 3 children in Pakistan cannot read a story in Urdu, while over 87% are unable to perform a two-digit division. This lack of ‘foundational learning’ presents a key challenge for both the education sector and the country as a whole.

What is foundational learning?

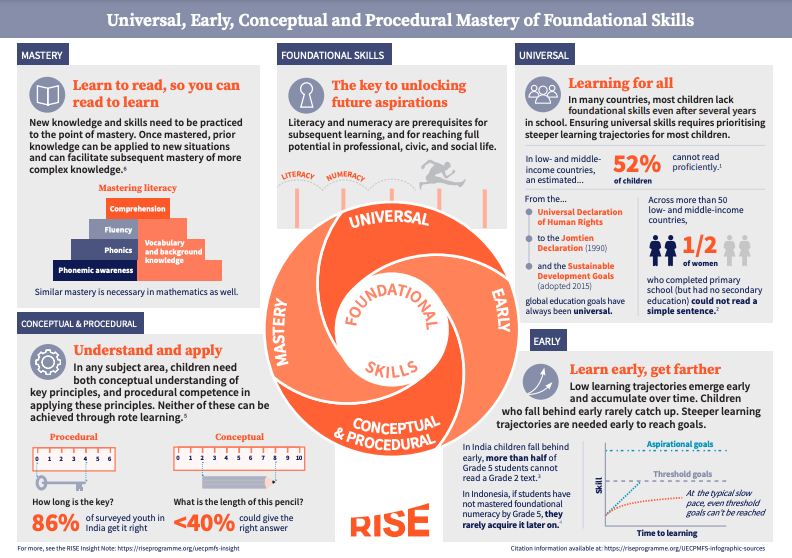

Foundational learning refers to “basic literacy, numeracy, and transferable skills such as socio-emotional skills that provide the fundamental building blocks for all other learning, knowledge, and higher-order skills”. These gateway skills are crucial for children to access quality education, a right guaranteed for every child and enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4). In the Pakistan Foundational learning Landscape Analysis, ‘foundational learning’ is described as “the attainment of basic literacy and numeracy skills at a minimum Grade 3-level proficiency, applicable to all children regardless of age or schooling status”. Typically, the ‘foundational’ stage includes two years of pre-primary education (ages 3-5) and Grades 1-3.

Why is foundational learning important?

Foundational learning is a basic right. Learning gaps disproportionately affect disadvantaged populations, limiting their life opportunities. Fostering foundational learning skills early on gives children a foundation for learning and development, cultivates critical thinking and enhances productivity. Furthermore, by contributing to better education and health outcomes for children, it helps foster stronger families through improved intergenerational opportunities that can shield them from poverty and vulnerability. Consequently, on a national level, foundational learning is essential for countries to achieve economic growth and development.

Figure 1: Foundational Skills Infographic (Belafi at al., 2020)

Why are children not learning?

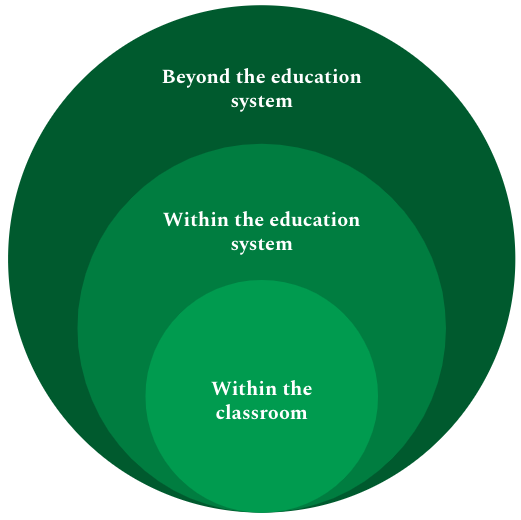

The Pakistan Foundational Learning Landscape Analysis has identified several barriers to foundational learning in Pakistan. Findings reveal a complex interaction of factors across many levels of the system, that is, within the classroom, within the education system, and beyond the education system.

Within the classroom findings include:

- Teachers often lack training in foundational learning, as existing pre-service and in-service programs emphasise generic skills as against essential literacy and numeracy competencies.

- Pedagogy prioritises outmoded teaching practices such as rote learning over critical thinking and relevant techniques such as phonics, reading comprehension, practical application and activity-based learning. Moreover, there is a lack of quality teaching and learning materials focused on foundational learning.

- The curriculum is too demanding for many; less than half of Grade 5 children can perform Grade 3 level reading and mathematics (ASER, 2023). This suggests that children who do not master foundational learning skills in the early grades struggle to keep pace in higher grades. Additionally, an overloaded curriculum compels teachers to prioritise syllabus coverage over foundational learning.

- Multi-grade teaching is pervasive with approximately 39-40% of public schools and 19% of private schools implementing some form of multigrading. This is a significant challenge for teachers.

- Children often learn in a language that is not their mother tongue, which can hinder their understanding.

There is limited and inconsistent use of formative and summative assessments tailored to measure foundational learning outcomes. - There is little dedicated time for foundational learning in the school day; schools dedicate just 40 minutes a day to ‘language learning,’ of which reading is only one element.

Beyond the classroom but within the education system findings include:

- Political commitment is essential to drive the system towards learning; Strong dedication and passion at the highest political levels are necessary not only to enroll children in schools but also to ensure they receive a quality education.

- Education governance is overly centralised and bureaucratic, leaving school leaders with limited agency and financial autonomy. Additionally, the process of selecting teachers is often politicised and lacks a merit-based approach.

- Financial allocation for education is low and inefficient; Pakistan spends only 1.7% of its GDP on education, and teacher salaries make up over 80% of education budgets.

- Parents need to be more actively engaged in their children’s education. Since children typically spend only 10-20% of their daily time in school, involving parents in children’s learning is essential, even if they lack strong foundational learning skills themselves.

Beyond the education system findings include:

- A rapidly growing population puts huge pressure on the education system; 7 million children will be born every year by 2040 in Pakistan, adding significant pressure to an already strained education system.

- The most underprivileged and marginalised learn little; an estimated 40% of Pakistanis are in poverty, and girls, the disabled, and rural children fare worse.

- Poor maternal and child health means that children’s brains do not fully develop; Over 40% of Pakistan’s children are stunted.

- Extreme vulnerability to climate change causes significant learning losses that are difficult to overcome. Pakistan is ranked as the fifth most climate-vulnerable country globally.

What can we do about it?

Urgent intervention is needed to address foundational learning gaps to improve children’s basic literacy and numeracy skills. The landscape analysis provides key recommendations for federal and provincial governments across Pakistan to take action:

- Support Teachers: Over 80% of education budgets are allocated to teacher salaries, although learning remains low. To drive foundational learning in a cost-effective manner, investment is necessary in specialised training for enhancement of teacher capacity and pedagogy, and incentives to attract good candidates. This includes providing high quality structured pedagogy packages (lesson plans, learning materials) and ongoing teacher training/mentoring. Improving assessment mechanisms is also crucial for regularly measuring students' actual learning levels and informing instructional practices.

- Strengthen the System: Policy makers need to ensure sustained political commitment to improve foundational learning. This can be achieved by designing foundational learning policy and planning frameworks for effective implementation and scaling; increased spending on basic education; dedicated funding for foundational learning; teaching children in their native language in the early years, and encouraging more parental and communal involvement in schools and children’s learning.

- Start Early: Encouraging cross-sectoral collaborations and interventions is crucial to increasing investment in education and health for young children and their mothers. Policymakers should also consider raising the allocation for Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) to at least 10% of overall education spending, to establish a dedicated budget for ECCE and enhance both the quantity and quality of pre-primary programmes.

To read more on foundational learning, please review our more comprehensive research in this area.

1) Pakistan Foundational Learning Landscape Analysis

2) Foundational Learning Policy Brief

Dr Zainab Salim is Senior Associate, Research at the Pakistan Foundational Learning Hub, Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.