The Patriarchal Political Order

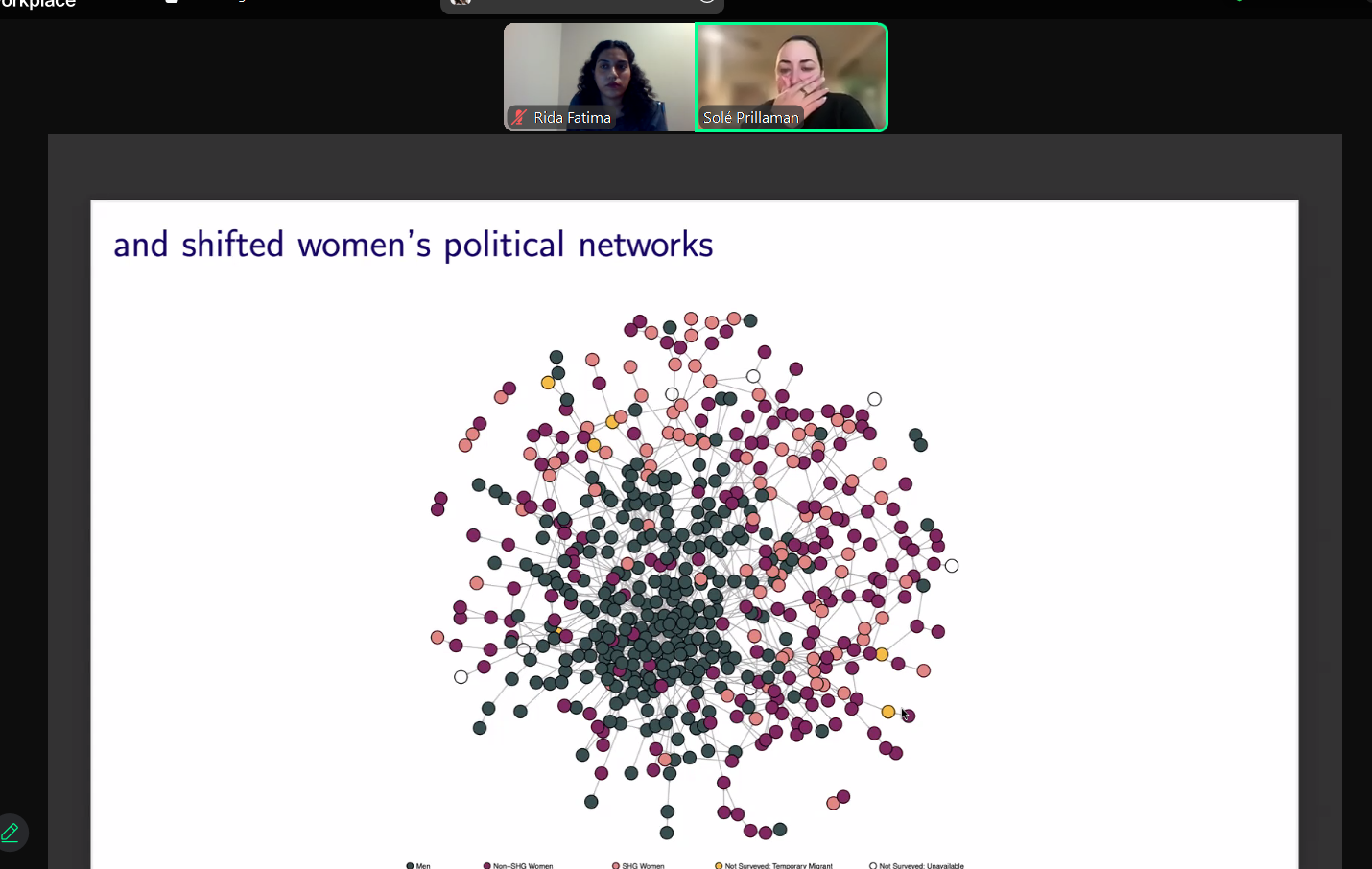

Dr. Prillaman noted that women participate more actively in politics when they gain autonomy from their households and build solidaristic ties through collective action. Her book is based on original surveys conducted in 2016 and 2019, 200 qualitative interviews, and an analysis of policies such as the mobilization of women's groups and gender consciousness-raising initiatives. These studies demonstrated that women’s groups can foster a sense of collective identity and shared purpose, thereby increasing political engagement.

Furthermore, Sharmeen Azeem (IDEAS) shared her research on EGAP Metaketa V: Women's Action Committees and Local Services in Pakistan that highlighted similar challenges in Lahore. The study showed that gender-based psychological constraints, like early socialization into traditional roles and limited opportunities for political involvement, hinder women’s participation. Differences in engagement levels were observed across localities; for instance, while Androon Lahore had dense social networks that facilitated participation, areas like the Railway Colony, home to working migrant women, faced significant barriers due to time constraints and lack of networks.

Dr. Prillaman addressed how trust and solidarity can be built among women in political groups. While acknowledging that women are a heterogeneous group, she emphasized that shared experiences—particularly those related to violence and gender inequality—can help overcome differences such as caste and promote collective action. However, challenges remain, including the sustainability of participation and ensuring effective facilitation for long-term change.

The discussion following the talk explored the role of men as gatekeepers in households, questioning whether the focus should shift to sensitizing men instead of placing the burden solely on women. Dr. Prillaman noted that while incentivizing men might bring some positive changes, achieving true gender equality might require deeper systemic transformations driven by women's collective efforts. Quotas can provide women with representation, but patriarchal structures often adapt to co-opt these new power structures and maintain control. Ongoing research in rural India showed that even with quotas, political decisions were frequently made by male family members. This reflects the need for expanded measures that go beyond institutional quotas to protect and strengthen women’s agency.

The webinar provided an enlightening discussion which underscored key questions about the sustainability of women’s political involvement, the importance of collective action, and the systemic changes required for gender equality in political participation.

Watch the full webinar here.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.