The Knot of Ecological Time: An Outlet, an Election, and an Irrigation Office

In 2015, local elections were held in Pakistan, ten years after the previous ones in 2005 during General Pervez Musharraf’s military rule. Local government elections have long been associated in Pakistan with military rule. For instance, attempts at “controlled democracy” such as General Ayub Khan’s, ushered in by the Basic Democracies Ordinance of 1959 that established an electoral college, have been seen as efforts to undermine political parties and their infrastructures of support (Cheema et. al. 2006). Sidestepping the well-studied question of whether local elections have been tools to entrench military rule, in this essay I invite closer attention to a different aspect and an unlikely site to study the electoral – an Irrigation bureaucracy. From here one sees the knotting of electoral and bureaucratic temporalities with those of water flow and the infrastructure through which it flows.

Radhika Govindrajan (2018) has recently made the important observation that commentary on electoral politics tends to restrict analysis to “the election moment,” the time before and immediately after an election. This, she notes, ignores other electoral temporalities, temporalities which may be pre- or post-election, and which are longer and less immediate. Thinking with bureaucratic time, Colin Hoag (2014) proposes a notion of “dereliction” in service of the larger claim that studies of bureaucracy decenter the outcome of bureaucratic practice. Infrastructural temporalities—of accretion, maintenance, incompleteness, suspension, or promise—have also been richly documented in recent ethnographic literature as constitutive of political action (Carse 2017; Barnes 2017; Gupta 2015; Hetherington 2014). Here, drawing on the insights of this corpus and material from my research with an Irrigation bureaucracy in Pakistan’s Punjab, I show that thinking with smaller elections and smaller temporalities reveals the knotted nature of everyday temporalities, and how a composite such as ecological time comes to be.[1]

At some point in the long summer of 2015, the Irrigation office[2] where I had been conducting research for about five months then, received two requests about the same case[3]—the case was a request for a new outlet (moga). One request was to expedite the case, and the other one was to delay proceeding on the case (“takheer ke saath”). The first one was made by a group of cultivators, and the second by the area MNA (Member of National Assembly).[4] An MPA (Member of Provincial Assembly) in the area was contesting in the upcoming local elections. The MNA of the ruling party, also the MPA’s party, contacted the Irrigation office and asked that proceedings in the case be delayed until the election. His reasoning, which suited the Irrigation office, was that if the Department proceeded on the case quickly—before the election had taken place—then he and his party workers would have no option but to put pressure on the Irrigation Department to decide the case in favor of the cultivators (i.e., to sanction the building of a new outlet). They needed the cultivators’ votes and therefore would have to try and get the new outlet built. The MNA specifically said: “Until the election our hands are tied.” If the Department let the election pass, then they could let the case proceed at its own pace, and not have to support it without it being “na-haq” (unjust).

That the application for a new outlet would be na-haq was a reference to a Department rule from some years ago stipulating that one outlet supply at least 1 cusec (measure of flow rate) discharge—with current “water allowances,” this meant that one outlet should irrigate an area of around 358 acres.[5] In multiple conversations with engineers, I was told it would be “impossible” to work around the rule. The revenue wing officials, however, tended to say that while it was impossible on paper, “off the record” it could be done: “It will be difficult but it can be and has been done.” The application was for a total area of around 290 acres.

The election took place and the MPA lost. The MNA was now free to act (“ab wo azaad hain”) —his party’s MPA had not been elected so he was no longer beholden to the cultivators. Conversations in the office revealed that there were still some possibilities – some stronger than others – for the cultivators to pursue the application for a new outlet. When I asked if the newly elected MPA would pursue the case for the new outlet, I was given a resounding no: “Because the new MPA knows they aren’t his voters. Everyone knows who votes for whom.” What other ways to get a new outlet were there, I wondered, other than through votes? There were two: sifarish (recommendation; request for favor) and money. Actually, it was a combination—the sifarish and money worked in stages. In the early stages, I was told, a case such as this one could advance through sifarish. But sooner or later money would be required.

In the meantime, however, these possibilities were not pursued as the two cultivators who were at the forefront of trying to get the outlet built had a falling out.

The 358 acres threshold is a measure of land—would it also be a measure of political community? The case was marked “pending” and deposited in a cupboard in the department office. Maybe the next election will change the outcome, some said. Maybe the two cultivators will reconcile and pursue this once again, others said. Maybe some other cultivators will take charge of the issue and begin to pursue it actively, still others said. “There may have been some developments in this case a few weeks ago, but you won’t find out for another month. And there won’t be more movement until Yaqoob sahib returns anyway,” I was told. Yaqoob sahib was the officer[6] overseeing the case and was away on a month-long leave.

Measures of Politics, Measures of Time

Why did this group of cultivators request a new outlet to begin with? I gathered two primary reasons: chaudhrahat and convenience. A Chaudhry is one who has sway, influence, power; a Chaudhry is a notable. It can often be used derogatorily, as in, “wadda aya Chaudhry” (Punjabi for “he thinks he is some big, powerful Chaudhry”). The Chaudhrahat in this case was tied to the ability to say, “We have our own outlet.” Also, to be able to say, “We got our own outlet. We don’t share an outlet, we have our own.” This case, if it succeeded, would strengthen the stature of those pursuing it.

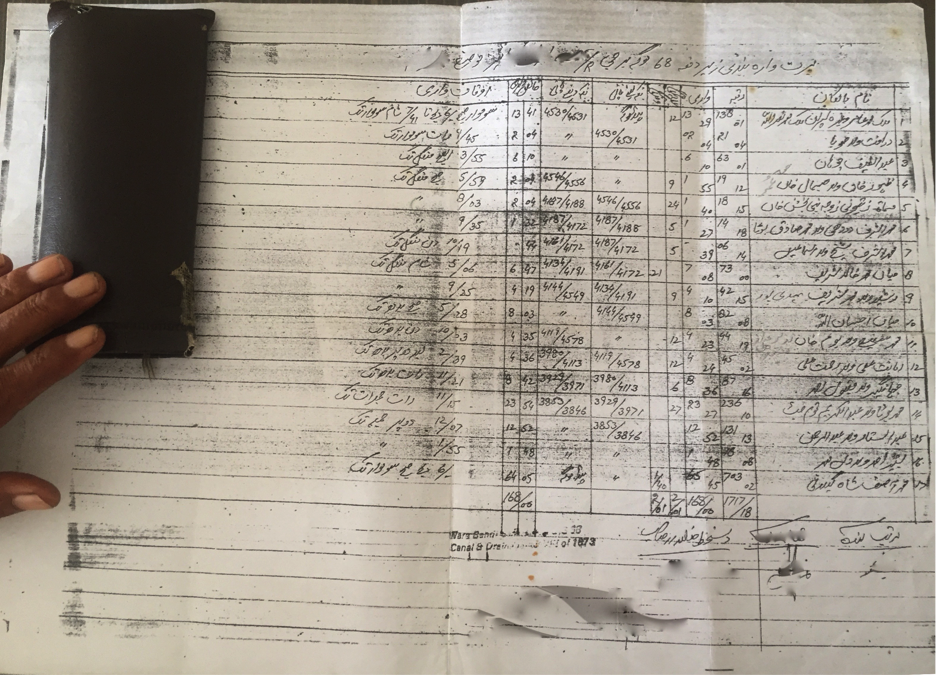

The convenience aspect has to do with how irrigation infrastructures entwine political and ecological temporalities. Let me illustrate by giving a brief description of how irrigation water is distributed among cultivators after it passes through the outlet. Each outlet operates according to a warabandi. The warabandi is the water rotation schedule for irrigation water—in this measurement regime, area of land corresponds with time-share of water. The time duration for each cultivator is proportional to the size of the cultivator’s landholding. The 168 hours of the week are divided by the area of landholdings (chakbandi) to be irrigated by an outlet. A water cycle typically takes 7 days, and it begins at the head and proceeds to the tail of the watercourse. During the cultivator’s turn (wari), the cultivator has the right to use all the water flowing in the watercourse. Each year at canal closure for desilting, the roster is moved by 12 hours so that night shifts become day shifts and vice versa.

In Figure 3 below, we see 3 nakkas, or apertures, with the two closed (one on either side of the watercourse) and the central nakka open. Whereas a nakka can be opened or closed, an outlet simply allows for passage. The central nakka is open because it is the wari of the landowner in the direction of the feet. The two nakkas on the sides have to be closed for all the water in the watercourse to pass through the central nakka during this particular wari.

What would happen to the existing warabandi if the new outlet were built? If the area to be irrigated by the old outlet decreases, so does discharge of water through it—timeshares, on the other hand, would increase. Let’s say a cultivator using the old outlet got seventeen minutes of water every week, for example. After construction of the new outlet, their turn (wari) would increase to more than 17 minutes. Since discharge has decreased, there is “overall” less water in the watercourse; therefore, time shares have increased. Irrigation officials frequently noted that this could be problematic in terms of “the public’s reaction” —if time shares increased then cultivators would have to “sit at the water” (pani key agay beythna parrey ga) for longer during their turn, needing to ensure that the closed apertures remained closed. This, too, was a bother and cultivators would prefer faster flows and, correspondingly, smaller time shares. Further, the more distant the outlet location from your land, the further off would you have to go to “sit at the water.” Area of land, volume of water, and labor time are entangled in the operation of this irrigation infrastructure.

The discharge of water from an outlet is a multiple of the area of flow (or, the orifice of an outlet) and velocity of water. The type of outlet matters when it comes to velocity. There are 3 types of outlets: modular/rigid, semi-modular (most common in Punjab), and non-modular. With a non-modular outlet, velocity depends on 2 factors: difference between the water level in the main channel and the water level in the watercourse. If the canal is flowing at full supply (agar neher full chal rahi hai) then discharge will be greater with such an outlet. For a semi-modular outlet, velocity depends on one factor: water level in main channel/canal. It does not depend on the water level in the watercourse. With modular/rigid outlets the discharge is what was designed—“they draw their designed discharge zabardasti [by force].” Here, discharge does not depend on the water level in the watercourse or main channel. There are few such outlets in Punjab.

If cultivators prefer faster flows because they reduce the time required to “sit at the water,” engineers prefer faster flows for another reason: water losses due to evaporation and seepage are inversely proportional to the velocity of flow. There is a deep division in opinion among engineers on seepage “losses,” with many arguing against canal lining so that aquifer recharge can be facilitated. The Indus Basin is the world’s second most “over-stressed” aquifer. Aquifer depletion, in turn, is connected with streamflow depletion (de Graaf et. al. 2019). Many such “losses,” transacted over long periods of time yield aggregate results such as depleting aquifers and underperforming irrigation infrastructures necessitating groundwater extraction (further depleting aquifers), in turn reducing streamflow. Ecological time, then, is a composite of more immediate temporalities. It is a knotting together of bureaucratic, electoral and infrastructural temporalities.

Anthropologists have creatively and comprehensively addressed the dialogical relationship between infrastructure and political subjectivities: for instance, we know how infrastructures of water delivery and control—pipes, pumps, water meters, faucets—become nodes between citizens and states, and sites where political subjectivities are forged (von Schnitzler 2013); how infrastructure maintenance is usually about much more than sustaining a particular infrastructural function—instead, it is one of many nodes in fields of socio-material contestation (Barnes 2017: 147-148); how infrastructures do not only connect nor are even designed to[7] as shown by Mona Bhan’s (2018) work on the potentialities of water infrastructure in a militarized setting; and how the varied mechanisms used to put pressure on bureaucrats—for example, through politicians—can make water flow in certain directions at certain times, but also compromise bureaucrats’ authority (Anand 2011).

Here, we see bureaucrats and politicians interacting in a way that shores up their authority to the detriment of some cultivators, and in favor of upholding a department rule. The possibility of an infrastructural addition provides succor to an election and a bureaucracy’s observance of a rule—letting the landowners think that it might be possible to work around the 358 acre-threshold enables the threshold to be upheld. This is a realm marked by multiple regimes of measurement. And this is a politics of measurement but also in measurement. The landowners seeking to obtain a new outlet have found common cause in being owners of contiguous holdings totaling, nearly, the 358 acres-threshold. A few more acres and the claim would have formal standing. At present, the threshold presents the possibility of getting a separate outlet, but also indexes the maneuvering that will be needed for it to go through. Is this a politics punctuated by area of landholdings, or is it generated by proximity to threshold? A measure of collective landholding size has become the horizon for political action. Until the 358 acres are reached, this is an inclusive, collectivizing politics to the extent that the contiguous landholdings are concerned. After that point it becomes an exclusivist, externalizing politics—or, to borrow from Antina von Schnitzler’s (2013) account of infrastructure qua political terrain, “non-public.”

Notes

[1] Evans-Pritchard (1940) distinguished “oecological time,” a concept of time that reflects relations to the environment, from “structural time,” a concept of time that reflects human relations to one another in the social structure (1940: 189). Social activities were of a “different order” and time had two movements, an oecological, or occupational, movement and a structural, or moral, movement. The times could be related – for instance, he described how the needs of the cattle translated oecological rhythm into the social rhythm of the year.

[2] In Pakistan’s Punjab province, withholding specifics.

[3] A “case” in common usage in this Department could be a reference to an issue at any stage of resolution and/or formalization.

[4] Of the 342 members of the National Assembly of Pakistan, 183 are from Punjab. The provincial Punjab Assembly has a total of 369 members. The population of Punjab is around 110,000,000. Roughly, an MPA has a constituency of 298,000 people (https://www.pap.gov.pk/members/stats/en/21). Accessed November 12, 2019.

[5] This is how the current Manual of Irrigation Practice of the department defines water allowance: “The outcome of all considerations of the duty of water, intensity proposed, crop ratio, water availability etc is the fixing of the water allowance. Water allowance [of each outlet] may be defined as the number of cusecs of the outlet capacity authorized per 1000 acres of culturable irrigated area.”

[6] Yaqoob sahib is a zillehdar. The Irrigation bureaucracy, broadly, comprises two wings: Engineering and Revenue. Zillehdars are the second lowest tier of officials in the Revenue wing, above the patwari (lowest tier). The Revenue Wing is responsible for assessing abianna (irrigation water charges), water dispute settlement among cultivators, and for “generally providing support” to the Engineering wing. All names and locations here are pseudonyms.

[7] https://culanth.org/fieldsights/ends.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Wenner Gren and National Science Foundation, and the American Institute of Pakistan Studies. I am indebted to Colin Hoag, Radhika Govindrajan and Ashley Carse for very helpful comments on earlier drafts. And to H sahib for the hours that went into the first time I could made something resembling Figure 2.

Works Cited

Anand, Nikhil. 2011. “Pressure: The PoliTechnics of Water Supply in Mumbai.” Cultural Anthropology 26(4): 542–564.

Barnes, Jessica. 2017. “States of Maintenance: Power, Politics, and Egypt’s Irrigation Infrastructure.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35(1): 146–164.

Bhan, Mona. 2018. “Jinn, Floods, and Resistant Ecological Imaginaries in Kashmir.” Economic & Political Weekly 53(47): 67.

Carse, Ashley. 2017. “An Infrastructural Event. Making Sense of Panama’s Drought.” Water Alternatives 10(3): 888–909.

Cheema, Ali et. al. 2006. “Local Government Reform in Pakistan: Context, Content and Causes.” In Decentralization and Local Governance in Developing Countries. P. Bardhan and D. Mookherjee, eds. Pp. 257–284. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

de Graaf, Inge M.E. et. al. 2019. “Environmental Flow Limits to Global Groundwater Pumping.” Nature 574: 90–94.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1940. The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Govindrajan, Radhika. 2018. “Electoral Ripples: The Social Life of Lies and Mistrust in an Indian Village Election.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 8(1/2): 129–143.

Gupta, Akhil. 2015. “Suspension.” The Infrastructure Toolbox (https://culanth.org/fieldsights/suspension). Accessed November 12, 2019.

Hetherington, Keith. 2014. “Waiting for the Surveyor: Development Promises and the Temporality of Infrastructure.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 19(2): 195–211.

Hoag, Colin. 2014. “Dereliction at the South African Department of Home Affairs: Time for the Anthropology of Bureaucracy.” Critique of Anthropology 34(4): 410–428.

von Schnitzler, Antina. 2013. “Traveling Technologies: Infrastructure, Ethical Regimes, and the Materiality of Politics in South Africa.” Cultural Anthropology 28(4): 670–693.

Originally published in Engagement. Engagement is the official blog of the Anthropology and Environment Society (AES), a section of the American Anthropological Association (AAA). You can read the original blog here

Maira Hayat is working on her book manuscript, Ecologies of Water Theft in Pakistan: The Colony, the Corporation and the Contemporary. Her research and teaching combine an interest in bureaucracy, law, political ecology and Islam. She is an Assistant Professor at the University of Notre Dame. You can read more about her work here.

Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre at LUMS

Postal Address

LUMS

Sector U, DHA

Lahore Cantt, 54792, Pakistan

Office Hours

Mon. to Fri., 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.